Going through a randomized supercuts of digital home videos my parents sent me during the first Christmas season of the pandemic, I held my breath in anticipation of my “dance recital.” A 7-year-old me prances to “Pretty Woman” between sheets hung from the popcorn ceiling tiles in my parents’ finished basement, spotlit by a single flashlight placed horizontally on a lightwood side table. My sister and our next door neighbors had choreographed the routines and produced the show, so to speak. While waiting, I expected the usual dysphoria-laced sense of second-hand embarrassment I had grown to associate with the recording. Instead, I was dumbstruck by an overpowering mix of tenderness, relief, and wonder met with my own cherubic face, beaming and looking so obviously adorned in my sister’s white dress, surrounded by the three older girls fussing around me to make sure everything was perfect. Pictures from only a few years ago open up an immeasurable distance between myself and the face looking back at me, but in that moment I felt inexplicably close to the version of myself on the screen. As my face moved closer to the camera, I became arrested by my own gaze: frozen with recognition looking at the same eyes I see today in the mirror looking back at me from almost twenty years ago.

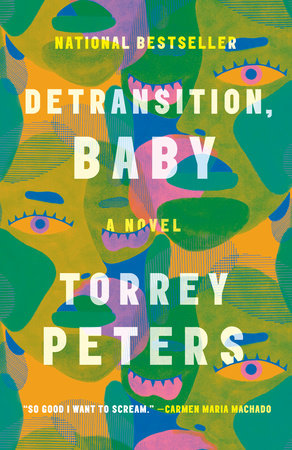

After the new year, I started laser hair removal on my face. On the way to one appointment, I stopped by McNally Jackson to pick up Torrey Peters’ Detransition, Baby which I had seen plastered up and down my Twitter timeline. At the time, I understood laser as a purely aesthetic and functional decision: I loved having smooth skin, hated the irritation from shaving and the subsequent in-grown hairs and breakouts that came with it. In the weeks after my appointments I brimmed with excitement watching the bulb-shaped follicles spread across my hands when I washed my face. My aesthetic yearnings metastasized after reading the novel’s description of facial feminization surgery. Soon after, I found myself analyzing facial structures — my roommates’, celebrities’, the few girlfriends’ I saw — and began remaking my own face in the mirror with a sense of wondrous possibility.

Detransition, Baby charts the intersecting lives of Reese, a trans woman living in Greenpoint, her now-detransitioned ex Ames (FKA Amy) and his boss, Katrina, whom he has gotten pregnant. Through Reese, Peters posits what is called “The Sex and the City Problem” wherein women grapple with the available paths for their futures: career (Samantha), relationships (Charlotte), a baby (Miranda) or expression through art (Carrie). However, as each of these possibilities is exponentially complicated for trans women, the SATC problem is largely aspirational as they default to a state of “No Futurism” brought on by the lack of blazed narrative arcs laid out before them. This informational drought not only affects how the world at-large views trans women, but also how we conceptualize possibility before and during transition. Amy considers this stereotypical portrayal as she waits to meet a crossdresser in her exploratory college years, expecting “Patrick Swayze in To Wong Foo [because] that was the best trans she’d seen on TV.” The narrator continues: “Her other options were Silence of the Lambs or The Bird Cage or maybe The Crying Game.”

Most children passively digest and incorporate schemas of gender, cis and trans, simply by existing in the world. And trans children, for their own survival, become deeply acquainted with expectations of gender performance, the rewards of staying on script and the punishments for straying beyond its allowances. Boys who become men and girls who become women are rewarded with increasing returns the more any person commits to their assigned bit. Self-preservation can then come by creating a perversion of transness to self-conceal and normalize. For me, this resulted in my gravitation toward damaged cis women characters who sought or needed transformation. When I got into Grey’s Anatomy, I wanted to be a surgeon in middle school. When I watched Dirt on FX I wanted to edit a gossip magazine. Shit, I almost went to grad school at Georgetown for public relations in the throes of a Scandal binge. The truth — obscured through the narrow view of normative desire — was simple: I wanted to be a woman. Consuming these stories satisfied a distal, directionless desire. It wasn’t until I came to stories about trans women by trans women that I could imagine closing the gap between “what can be wanted and what can be said.” Detransition, Baby made me think of my gender as something other than an island I was stuck on: as a point of relation rather than evasion, which was how I had calibrated it to keep an arm’s length away from the crushing dysphoria of masculinity.

Three months and two laser appointments later on my 25th birthday I was texting my sister about starting hormones while I waited for the LSD to hit with my friend Taylor in a rented penthouse in Sunset Park. Growing up, I spent as much time with my older sister and her friends as she’d allow. Perhaps this is why she was the first person I told. I think in some way I was telling her again that I wanted in on girl time and, this time, she welcomed me with open arms rather than closing the door in my face—as older sisters often do with younger brothers.

I brimmed with excitement watching the bulb-shaped follicles spread across my hands when I washed my face.

After a day of dancing to Janet Jackson on the balcony and taking a flower bath together with Mariah Carey playing in the background, Taylor and I watched Miss Congeniality while we came down. As a child, I would re-enact for comedic effect the scene where Agent Gracie Hart (played by Sandra Bullock) struts out of an airplane hangar to “Mustang Sally.” She’s waxed from head to toe, hair blown out, wearing a periwinkle bodycon dress. Her transformation into femininity almost seems too much until she trips and subsequently falls out of the camera frame. This time, I felt a twinge of sadness in the moment of her tripping: here is a woman, rarely seen as such, finding her femme legs for the first time. Her stumble is played for laughs, a script I had subconsciously internalized and regurgitated.

On this viewing I was struck by how trans the movie is: the first act when Agent Matthews (Benjamin Bratt) tells Hart that “nobody thinks of you that way,” as in not as a woman; the emotional climax when the two debate the value of “throwing out the rule book;” and Hart’s intervening acclimation to girlhood and subsequent graduation into womanhood. I mean she even gets a new driver’s license with a new name: Gracie Lou Freebush. In a scene about halfway through, Hart takes mock interview questions to prepare for the pageant. Her coach points to her lack of personal life and relationships: “You have sarcasm and a gun.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

SubmitYOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

As time goes on and my transition deepens, I continue revisiting my favorite films. I see this forced-femme reluctant cis girl makeover trope across the first ten or so years of my life, each having served me as a less potent substitute for explicitly trans narratives. There’s Tai’s red hair being washed out by Cher and Dionne in Clueless (1995). Violet (played by Piper Perabo) revamps her wardrobe with Cami by way of Lil in Coyote Ugly (2000) the same year Miss Congeniality came out. And then there are Anne Hathaway’s aesthetic transitions in the Princess Diaries (2001) and again in The Devil Wears Prada (2006). If these “failed” women could transform themselves into some glossier, feminized, more acceptable version of themselves, maybe I could too one day.

In a flashback scene in Detransition, Baby, college-aged Amy sits in the car on the way to a fetish store when the older man talks about Fictionmania, a site where thousands of anonymous writers would contribute stories of women forcibly feminizing boys through aesthetics, surgery and magic, followed by a hefty dose of humiliation and degradation. Discussing it offers Amy a sense of disclosure laced with disgust. Not until Amy is discussing outfits with the store’s trans cashier does titillation give way to something sincere through “her inclusion in that feminine rite.” The scene makes me think of the day my sister or one of her friends painted a single thumb nail of mine blue and I told people that they had bet me about how long I would keep it, all the while cradling it in my mind’s eye, basking in the energy radiating up my arm.

Boys who become men and girls who become women are rewarded with increasing returns the more any person commits to their assigned bit.

Few things feel as demoralizing as openly wanting something that isn’t in arm’s reach. It’s for this reason I will never run to catch a bus or be a contestant on Love Island; To be seen desiring so plainly is humiliating. For Amy, forced feminization at the hands of beautiful women dilutes the sincerity of her desire and preempts any external debasement by injecting it into the fantasy, allowing a safe (and secret) place to find some small release. For our 2000s made-over romcom girls, their hesitance, indifference or disdain stems from the same emotional location: they aren’t sure if they can be the woman in the “after” picture. The gap in aesthetics and, more importantly, in knowledge is insurmountable. Our shared degrees of removal from the truth of our most intimate desires — Amy’s fantasy, Hart’s cynicism and my sense of attraction to these made-over women — allowed us to inch toward the cliff’s edge without copping to the urge to jump. They allowed us, for a time, to keep our desire for transformation a few degrees removed from our persons. What ultimately shook us out of our restrictive systems of relating to femininity was making connections with actual real-life women.

Miss Congeniality and Detransition, Baby made me realize that womanhood is a gift given by women and reciprocated between them. Hart, at first, can be seen as the receiving party, accepting Miss Rhode Island’s invitation for a late night cocoa. Once her teams abandon her in the top 5 and the FBI investigation is closed, the other girls rush into her dressing room mirror to help her apply her makeup. Through her blossoming friendship with Cheryl, Hart learns that Miss Rhode Island, in her awkward sincerity, also never felt like she had access to that sense of peak femininity, represented by both the red pair of “satan’s panties” she stole from the store when her mother wouldn’t buy them and her inability to see herself as the girl doing a sexy dance with flames exploding from her batons. Hart is then able to reciprocate Cheryl’s warm welcome into girlishness when she surprises her with flaming batons before the final talent competition. This invitation into, and exchange of feminine intimacy — the sharing of knowledge and possibility, tips and tricks — happens in ways big and small, like writing a book or helping a baby trans in the dressing room at a fetish store.

Miss Congeniality and Detransition, Baby are both stories about making it off the island of rigid gender, the forging of intimacy through feminine rites of passage and articulating the potential for healing through matrilineal bonds and the isolating effects of their absence. Cultivating a relationship with the feminine allows Hart to establish romantic and platonic relationships where before they couldn’t exist. Detransition, Baby operates at the intersection of lost and found maternal lines. Katrina — whose maternal grandparents shunned her mother when she chose to marry a white man — conceptualizes her baby-to-be with Ames as “a chance to connect my mother to my child, to relink the maternal line that my birth broke”. Reese and Ames don’t speak to their mothers, but Reese is a mother figure to Ames, or rather to Amy. In an extended metaphor, Ames explains the relative location of the generation of trans girls “who basically invented screaming online” by likening them to juvenile elephants whose mothers had been shot by poachers. She articulates the impact left by the missing generation(s) of trans women lost to violence, stealth living, the closet and/or AIDS. It’s this vacuum of lived experience that sent me to Miss Congeniality, Amy to FictionMania and keeps the “Sex and the City” problem out of reach for many trans girls.

Detransition, Baby was my red pill. You could say it fully cracked my egg. In the year since I read it, I ran through a litany of other work by trans women while banking sperm, starting hormones and coming out (again) to my friends and family. It’s a testament to the infancy, importance and vulnerability of a trans canon that a single story can alter someone’s life so completely, something Peters herself knows well enough. On the backside of a galley for Imogen Binnie’s Nevada, Peters is quoted: “Nevada is a book that changed my life: it shaped both my worldview and personhood, making me the writer I am.” The two novels are intertextually connected: through their invocation of forced femininity smut, but also through their exploration of how the medicalization of trans femininity through male desire corrupts the psychic grappling of its young trans characters who don’t know they are such.

Nevada depicts a trans girl in Brooklyn, Maria, who breaks up with her girlfriend, steals her car and drives across the country with a bunch of heroin, where she meets James, an 18-year-old who jerks off to forced femme erotica. Originally released in 2014, it slowly went out of circulation after its publisher folded. What followed is a classic tale of economics: As the creation of trans stories continues to lag behind demand, the value of Nevada skyrocketed. Online the asking price for used paperbacks went up to several hundreds of dollars. In a version of the afterword for MCD’s reissue of the novel published in The Paris Review, Binnie writes that “People have called Nevada ‘ground zero for modern trans literature,’” but for a time it had literally been lost in the industry shuffle.

As the digital worlds within these novels outline self-determined trans discourse, the books themselves represent solutions to the problems they articulate.

Detransition, Baby, Nevada and the referential materials contained within them emphasize the importance of tending to our stories and communities making connections through the digital world as well as the physical one. Through the literary landscapes of Nevada and Detransition, Baby, readers can trace the digital development of communal trans culture from Maria’s blogging on LiveJournal, the roots of Amy’s awakening on FictionMania to my own which began with pictures of Detransition, Baby on Twitter. As the digital worlds within these novels outline self-determined trans discourse, the books themselves represent solutions to the problems they articulate. For me at least, these novels offered instructional information of “doing trans” rather than stalling out on the semantics of what it means to “be trans”. Maria taught me to splash super hot water on my face to get the closest shave. Amy taught me that it’s best to walk with your hips tucked under your spine, swinging them laterally. Connecting to a trans feminine creative tradition not only allowed me to more fully reconnect with the women characters I have always been drawn to, but also opened the door to more meaningful relationships to the women around me. What writing and being trans have in common are that they are, in practice, nauseatingly sincere, which might be why one naturally led me to the other. Though it started a long time ago when Gracie Lou Freebush and the girls like her taught me that femininity wasn’t something innately built into any one person, but something that can be cultivated in each of us, something that is best cultivated between us. I feel it when I’m getting a complimentary facial from the esthetician who does my laser. I feel it when my friend paints my right hand’s nails because I can only do the left. I feel it when I put on makeup in the mirror with the girls the hour before a show. This sororal camaraderie at one time existed between me and characters on film, but now it is contained between me and the women in my life, in the palm of my hand.

As I got off the highway, driving upstate to my sister’s bachelorette party six months after my 25th, there was a very light rain and the sky was a pleasant gloomy grey, with streaks of light cutting through above the green hills and fog-laid valleys. I cracked the window to feel the stream of fresh air and see if it still smelled the same. At one intersection, I saw three little girls that reminded me of my sister and our next door neighbors, who produced my recital back in the day. It was with their family that we used to travel up to Keuka Lake in the summers (where an unfilmed recital to “Smooth” by Santana had taken place). In fact, the last time we went there, and for the first time in years at that point, I had just cut my long middle school hair into a more acceptable spikey-buzzed fade for high school. I tried to slow my tears as my arrival time inched closer. My eyes were only a little red by the time I pulled up to our rented chalet.

I saw my non-blood aunts sitting at the long wood table between my sister’s bridesmaids, our friends. I turned and met my sister’s blue eyes and fell into her arms as a new wave of tears crashed into the tightest hug we had ever shared. She led me downstairs with my mother, where I did the same to her. I didn’t know what to say — I didn’t know what I was going to say — but what came out of my mouth was relational: I am your daughter.