OMIC Underwriting Manager

Digest, Summer 1999

Technological advances, demographic shifts, and socioeconomic forces over the past decade have brought about profound changes in the practice of ophthalmology and the resulting liability exposure. Through the years, OMIC has responsibly modified its coverage features and liability limits to meet these changes.

Refractive Surgery

Until 1995, virtually the only surgical option for treatment of myopia was radial keratotomy (RK). Then in 1995, the FDA approved the Summit laser for photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). Since that time, LASIK has essentially become the procedure of choice for many. Meanwhile, several other refractive surgery options have emerged, and OMIC has extended coverage to insureds who perform these procedures: RK/AK, PRK, ALK, LASIK, Intacs, Clear Lens Extractions, and Phakic Implants for refractive purposes.

In the past year, OMIC has modified at least six existing guidelines for refractive surgery and developed guidelines for Intacs. Recent policy modifications include:

The maximum degree of myopia for PRK and LASIK was increased in recognition of changes in FDA-approved guidelines.

The minimum age for PRK using the Summit laser was lowered to 18.

The required one-week interval between primary PRK and LASIK procedures may be waived for experienced surgeons who qualify, subject to special consent requirements.

The 10 surface PRK requirement was discontinued to allow physicians with limited or no prior PRK experience to qualify for LASIK coverage provided they are certified on the laser and are proctored for their first five LASIK cases.

Cosmetic Surgery

Many ophthalmologists have expanded the scope of their practice to include laser skin resurfacing, laser hair removal, and other cosmetic surgery procedures, including facelifts and liposuction. Subject to underwriting review and adherence to guidelines, coverage for such cosmetic procedures is now available to qualified ophthalmologists.

Part-time and Tail Coverage

While OMIC has always offered part-time rates to ophthalmologists who limit their practice to medical ophthalmology, recently this discount was extended to qualified insureds who perform surgery as well. Eligibility for a part-time discount is based upon the number of practice hours, scope and volume of practice, and claims history, among other things.

Recognizing that an increasing number of ophthalmologists may elect to retire at an earlier age, OMIC discontinued its age requirement for free tail coverage upon retirement and, more recently, reduced the length-insured requirement. Now, an insured who retires permanently from the practice of medicine at any age qualifies for a free tail provided he or she has been continuously insured with OMIC for at least one year (see note below). OMIC also provides a free tail upon death or disability, regardless of age or length of time insured with OMIC.

Liability Limits

Legislative changes have prompted requests for more flexible coverage options in certain states. OMIC now offers limits of $400,000 per claim/$1,200,000 aggregate to insureds who practice in Pennsylvania; $250,000/$750,000 in Indiana; and $1,500,000/$4,500,000 in Virginia. OMIC also considers, on a case-by-case basis, requests by insureds for non-traditional limits. (Note: the limits noted here applied in 1999 – limits in PA and VA have increased since this article was written)

New Entity Exposures

OMIC realized the need to develop guidelines accommodating the liability exposures associated with shared management of post-operative patients. OMIC will directly insure qualified employed optometrists as additional insureds under the physician’s policy and, in certain limited circumstances, may extend coverage to the entity and/or optometrist in cases where the optometrist owns a portion of the practice.

To remain financially viable, ophthalmic surgery centers often must allow other specialists to use their facility. Thus, OMIC has developed appropriate underwriting guidelines and rates that permit the company to insure the surgery center for its vicarious liability exposures arising from ophthalmic and non-ophthalmic procedures. At the request of an insured network, OMIC also developed a program for coverage of qualified eye banks.

Fraud and Abuse Coverage

In response to the federal government’s zealous efforts to root out health care fraud and abuse, OMIC now provides its professional liability insureds with a Medicare/Medicaid Fraud and Abuse Legal Expense Reimbursement Insurance policy free of charge. Academy members insured elsewhere for their professional liability coverage may purchase fraud and abuse coverage from OMIC for a nominal premium.

For more information or to request changes to your coverage, please contact any of OMIC’s Underwriting Department representatives at (800) 562-6642. For information regarding OMIC’s fraud and abuse coverage, please contact Kim Wittchow at ext. 653.

UPDATED (1/13/2013): OMIC’s retirement premium waiver was modified in 2003 to increase the required minimum period of continuous insurance from 1 year to 5 years for all new policies incepted on or after 6/1/2003 and for all individual insureds added to existing group policies on or after 6/1/2003.

Coverage Issues // No Comments

By Michael Meyers

Mr. Meyers is a freelance writer in Charlottesville, VA. He has written extensively about the insurance industry.

[Digest, Fall 1999]

Most doctors and other professionals would never dream of going without life, auto, homeowners, and medical insurance for their families. Yet they risk the assets they’ve worked so hard to build up by overlooking another equally important personal insurance protection: long-term care insurance. They often believe that a nursing home represents a loss of independence, that it is the only form of long-term care available, and that long-term care insurance is too expensive.

Nursing homes are not the only long-term care option. More and more people are taking advantage of assisted-living facilities, senior housing with services, adult foster care, home health care, and other innovative forms of long-term care to avoid the high cost of a nursing home stay. According to the Health Care Financing Administration, the average annual cost of a nursing home stay is $47,000 and rising. Of course, the cost of alternative services can add up quickly too, and even a single year of long-term care paid for out-of-pocket can be more costly than insurance.

Changes in federal income tax incentives in 1997 allowed qualified long-term care insurance premiums to be deducted as medical expenses, in whole or in part, subject to certain limits, provided the plan meets federal guidelines. Employers who pay premiums for an employee and/or spouse can deduct them as a business expense. Solo practitioners or doctors in a partnership, including S corporations, may deduct long-term care premiums to the same extent they do health insurance premiums.

The younger a person is at the time long-term care insurance is purchased, the lower the premium. Many people wait too long to buy this coverage. Not only does this raise the premium, it increases the likelihood of developing a chronic illness that will disqualify the applicant for coverage. When evaluating the need for long-term care insurance, take into account the individual’s personal situation, retirement plans, and family relationships. Ask yourself the following questions:

How Long Should Coverage Last?

Given the statistics on lengths of nursing home stays, you probably want to shop for a long-term care policy that provides two to four years of care. More coverage may be a waste, less a big risk.

How Do I Decide on a Daily Benefit Amount?

Research the costs of nursing home care where you live, keeping in mind that it is likely you will need to pay a nursing home more than the basic rate each month because of added charges for drugs and special services. One approach is to select a daily benefit equal to the nursing home’s published rate and plan to pay out-of-pocket for extra services. You also may want to take into account your projected discretionary income and how much you will be able to afford to pay out-of-pocket.

How Much Can I Afford Out-of-Pocket?

Even with this insurance, you will have to pay some costs yourself. First, you must meet a deductible (elimination period). Then, some plans pay a fixed amount for each day you are in a nursing home, regardless of how much your nursing home care cost, while other plans pay actual charges up to a fixed amount. How a plan pays its benefits will influence how large a benefit you select, so factor this into your decision.

What Coverage Benefits Should I Look For?

The company behind the coverage. The carrier’s financial stability and experience providing long-term care insurance are the first things to consider. You want assurance that the company will be around in ten or fifteen years if you need to apply for benefits. A.M. Best, Moody’s, or Standard & Poor’s rating systems can help you judge.

Type of coverage provided.

Look for a plan that covers skilled, intermediate, and custodial nursing home care.

Home health care.

You’ll most likely want a plan that offers home health care as an option or as one of its regular benefits in situations where nursing home care is not necessary.

Definition of a covered stay.

A good plan should cover your nursing home stay not only if you are injured or sick but also if you need continual help with two “activities of daily living” (i.e., dressing, toileting, continence, transferring, or feeding) or you need supervision because of cognitive impairments like Alzheimer’s Disease.

Choice, choice, choice.

Different people have different needs based on their income and assets, nursing home costs where they live, and how much they can or want to “self-insure.” Select a plan that gives you a choice of daily benefit options, elimination periods (deductibles), and benefit limits. That way you can build a plan to meet your individual needs.

Inflation protection.

Because you are purchasing insurance today to meet tomorrow’s costs, you probably will want inflation protection. There are two types of inflation protection available: one automatically increases your benefit level by an equal percentage each year; the other compounds the benefit increases.

Guaranteed renewable.

This means you can always renew your coverage as long as you pay your premiums on time, even if your health condition worsens. In most cases, however, the insurer will reserve the right to change premiums for all persons in a given class or state.

Waiver of premium.

This allows you to continue coverage without cost after you have been receiving benefits for a certain period of time, such as 90 days. Some plans offer a “return of premium” or nonforfeiture benefit in case you die or terminate your coverage. However, this provision can add significantly to the cost of a plan.

If you need additional help shopping for long-term care insurance, contact the National Association of Insurance Commissioners at (816) 374-7259 for a copy of the Shoppers Guide to Long-term Care.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology offers comprehensive long-term care plans to active Academy members and their spouses, parents, and grandparents. To learn more about these plans, call the Academy Insurance Center at (800) 906-7607 for a free consultation.

Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

By Betsy Kelley

OMIC Underwriting Manager

[Digest, Spring 2000]

Contracts are a fact of life in most ophthalmic practices today. Providers sign contracts with health care plans, laser centers, finance companies, and other entities. Contracts outline each party’s responsibilities, compensation, and other terms. In many instances, contracts may include provisions that affect a provider’s professional liability exposure.

One provision frequently found in contracts is a hold harmless or indemnification clause whereby one party (usually the physician) agrees to contractually assume the liability exposure of the other party. Some indemnification clauses are quite broad, requiring that the physician hold the other party harmless for “any and all claims, suits, losses, or damages” arising from services rendered, without regard to which party was responsible for such activities or whether negligence was involved.

Other clauses are sufficiently narrow and require that the physician hold the other party harmless only for “claims, suits, losses, or damages arising solely from the physician’s negligence and not otherwise covered by insurance.” Indemnification clauses may be unilateral, meaning that only one party holds the other harmless, or they may be mutual, meaning that both parties agree to hold the other harmless for its own negligent actions.

OMIC provides limited contractual liability coverage within policy limits for indemnity and reasonable defense costs that insureds become legally obligated to pay pursuant to a hold harmless or indemnification agreement in a written contract between the insured and a hospital, health maintenance organization, preferred provider organization, or other managed care entity. This coverage is limited to indemnity and defense costs incurred solely from the performance of professional services provided by the insured and is solely for medical incidents otherwise covered under the policy. In certain circumstances, OMIC may, for an additional premium, extend contractual liability coverage by endorsement to other entities that are not engaged in the practice of medicine but may incur liability exposure as a result of their relationship with the insured.

OMIC’s policy excludes coverage for liability assumed under contract with other types of organizations if such liability would not exist in the absence of the contract. Therefore, OMIC generally recommends that indemnification clauses be removed from the contract, if possible. If the clause cannot be removed, OMIC recommends that it be replaced with a narrow, mutual hold harmless clause in which each party agrees to indemnify the other for losses arising solely from the party’s negligence.

Additional Insureds

A new trend is emerging in which organizations are no longer satisfied merely having the physician contractually agree to hold them harmless in the event of a claim. Instead, they are now adding clauses to their contracts requiring that the physician name them as an additional insured under the physician’s policy.

OMIC is generally able to name a third party as an additional insured only in situations where the entity is a management services organization (MSO) involved in administrative activities such as the purchase of equipment, billing, and other matters. Because they do not render medical services themselves, such organizations are frequently unable to purchase medical malpractice policies of their own.

With the exception of MSOs, OMIC will not name third parties, such as medical professional corporations or laser refractive centers, as additional insureds. Because these organizations render professional services themselves and are likely to be responsible to some extent for supervision and control of the physician’s activities, they are equipped to insure themselves or to purchase separate coverage for their liabilities. It is generally in the best interests of both parties to purchase their own insurance policy so separate limits apply. Otherwise, each party’s limits are reduced by any indemnity paid on behalf of the other party.

Other Provisions

Other contract provisions may specify the limits of liability that the physician must carry or may require that the physician provide evidence of insurance. Upon request, OMIC can issue a certificate of insurance to the organization, specifying the insured’s policy number, effective and expiration dates of coverage, and limits of liability. In addition, OMIC also will attempt to notify the certificate holder of any material changes in coverage, such as a change in limits or cancellation of coverage. Some contracts may require that the organization be provided with advance notice prior to cancellation or coverage changes. Although OMIC will do its best to provide ample notice to certificate holders, OMIC itself may not receive sufficient advance notice of requested changes to comply with such contract provisions. For this reason, such requirements should be removed from any contract.

As a service to its insureds, OMIC will review contract language*** as it relates to professional liability issues and provide advice regarding uninsured risks. To have OMIC review these contract provisions, contact the Risk Management Department at (800) 562-6642, ext. 603 or fax the specific clauses to (415) 771-7087.

*** NOTE: OMIC no longer reviews contract language. However, as a service available only to its insureds, OMIC will provide an analysis of indemnification agreements prepared by our Legal Counsel. Policyholders may share this analysis with their own attorney. To obtain this analysis, contact the Underwriting Department at (800) 562-6642, option 1 or via email at underwriting@omic.com, or the Risk Management Department at (800) 562-6642, option 4 or via email at riskmanagement@omic.com. 10/8/14.

Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

By James F. Holzer, JD

Mr. Holzer is OMIC’s President & CEO.

[Digest, Winter 2001]

The U.S. economy and stock market may be showing signs of renewed vibrancy this quarter, but malpractice insurance carriers are bracing for the worst. Physicians in all specialties are seeing professional liability rates skyrocket for the first time in many years. It’s a grim reminder of when so-called malpractice crises erupted in the past, driving doctors to pay higher premiums, find replacement, and seek shelter behind defensive practice patterns.

Although ophthalmologists are not immune from current adverse developments, their loss experience is better than most other specialties and, in some cases, significantly better on average than all specialties combined. OMIC’s loss experience and financial performance continues to be more favorable than the industry as a whole. Yet claims costs and related expenses require even the most conservative carrier to periodically adjust its price. A few physician-sponsored carriers have been able to keep rate increases well under the 10% this year. OMIC, for example, will adjust its premium by 7.5% for policies issued or renewed after July 1, 2001.

The news unfortunately isn’t as good for other physicians. Double-digit rate hikes are back. Many medical malpractice carriers anticipate or have already instituted premium increases that may well exceed the expected national average of 15%. Commercial (non-provider-owned) carriers seem the hardest hit with planned increases of 50% to 100% in some states. Although the relative rate for an ophthalmologist is less than say for an OB-GYN specialist, some of these large increases may apply across the board to ophthalmologists insured by these companies. One large national carrier, which has slipped from first to fifth place as the leading provider of malpractice insurance, reportedly doubled its premiums for some ophthalmologists in Arizona, Missouri, and Texas and selectively levied a 60% increase for risks in Vermont and 75% in California. Another large national provider of physician professional liability insurance isn’t writing or renewing business at any price in Georgia, sending many of its longtime policyholders and insurance brokers scrambling to find replacement coverage.

Physician-owned or sponsored insurers seem to be faring better. Rate announcements from doctor-owned carries range from no increase to 30% with some 40% to 50% increases in so-called problems states such as West Virginia. Insurance companies there were created by medical societies and governed by physicians mushroomed in the 1970s and 80s in response to capacity and affordability problems during prior hard markets. Collectively, these companies now provide professional liability coverage to nearly two-thirds of the physicians in the U.S. Based on year-end 2000 financial statements, this physician-controlled segment of the insurance industry has generally done better than the medical malpractice industry as a whole., which includes the large commercial stock companies.

Rapidly Deteriorating Market

In a recent study, a leading research analyst for the insurance industry, Conning & Company, warned that the financial condition of the medical malpractice insurance business is rapidly deteriorating with “no margin for negative surprises.” Looking at the industry as a whole, it estimates a huge deficiency in malpractice claims reserves to the tune of a staggering $1.7 billion. This degree of adverse development clearly doesn’t happen overnight. Conning suggests the problem began as early as 1993 when the severity of incidents, accelerating claims payments, and increasing defense costs started to climb. Of particular concern as the rising incidence of claims alleging failure to diagnose and medication-related errors. Ophthalmologists should not be quick to assume that such problems don’t apply to them. A number of OMIC’s largest settlements have related less to the science and practice of ophthalmology and more to general medical problems such as failing to diagnose cancer or failing to adequately track and follow up on urgent care. Clearly, failure to follow some of the most basic risk management principles of general medical practice could have a more crippling effect on overall ophthalmic loss experience nationwide than some of the newer refractive procedures such as LASIK, which to date show only low to moderate claims severity.

What’s causing this deterioration and why does it seem to be occurring so suddenly after years of declining malpractice rates and aggressive competition? For at least the past five years, many medical malpractice carriers have had a voracious appetite for market share. This has had the effect of driving prices down even though combined and operating ratios for the industry as a whole were locked in a steady upward creep. Fortunately, physician-owned/sponsored carriers such as OMIC have been able to maintain more stable and consistent ratios during this period.

Nevertheless, during these “soft market” conditions, the financial results of carriers were propped up by good investment returns, favorable reinsurance deals, and better-than-expected loss results from prior policy years, which allowed companies to reduce their reserves and increase surplus. In the background, however, malpractice claims severity continued to grow. Defense costs kept rising, reserve takedowns on older policy years began to dry up, investment returns started to shrink, but premiums on the most part remained the same. Malpractice carriers were still locked in a battle to gain a shrinking market share. Artificially depressed rates prevailed until the damn burst at year-end 2000.

Loss Ratios Worsen

Every spring, insurance carriers file detailed financial statements showing the results of their operations through December 31 of the previous year. As analyst look at these year-end 2000 statements, a collective picture of the industry began to emerge. Their suspicions during the past 24 months are being confirmed. The approaching “hard market” has finally arrived. Loss ratios, which measure a company’s loss experience in relation to its total book of business, jumped nearly 10 points in one year to approximately 100% for all doctor-owned carriers combined. Analysts expect the numbers to be worse when large independent carriers are included in the mix. (OMIC’s loss ratio in comparison increased only 2.5% to 79.9% at year-end 2000.)

Other ratios that analyst use to measure an insurer’s operating performance also worsened during the past year. The combined ratio, which measures a company’s overall underwriting profitability before investment returns, climbed to 125% for the provider-sponsored carriers and 134% for the entire industry. However, after factoring gains on investments, carriers still showed relatively acceptable (albeit increasing) operating ratios. An operating ratio of less than 100 indicates acceptable financial health for a carrier because it is still able to show a profit from its core business. The average operating ratio for all doctor-owned carriers combined was 95.6% at year-end 2000. (OMIC reported a combined ratio of 119.3% and a favorable operating ratio of 91%.)

More Ominous Signs for Some Carriers

Unfortunately, we are now starting to see a number of long-standing carriers having difficulty even measuring up to the average. Data from financial filings for year-end 2000 indicate that between one-quarter and one-third of provider-sponsored medical malpractice carriers may show an operating ratio of greater than 100% and could report negative operating cash flow. A handful of companies may even show operating ratios in excess of 120%. A number of large independent commercial carriers also are facing significant challenges. The health care unit of one of the leading national medical liability carriers reported a year-end 2000 combined ratio of almost 130% and a fourth quarter combined ratio of nearly 160%. A large hospital association carrier reported a combined ratio last year of 200% as well as receiving two rating downgrades by A.M. Best Company in as many years.

Even if an improving U.S. economy turns Wall Street bullish again, it’s clear that it will take more than higher returns on investments to reverse the deterioration of some segments of the medical malpractice insurance industry. Insurance carriers will have to invoke a number of tough and unpopular remedies to exorcise the demons of the hard market of 2001. Here’s what ophthalmologists and doctors in all specialties can expect:

- Higher malpractice premiums for the near future. The size of increases will vary by carrier and depend on an individual company’s financial performance and overall profitability. OMIC anticipates a more modest fluctuation in its rates compared to the industry because it has historically kept rates a level sufficient to support its ability to pay claims over the long term.

- Tougher underwriting and cancellations of policies that carriers deem unprofitable. Some carriers appear to be engaged in wholesale cancellation of policies based primarily on geography, claims history, and scope of practice. Some uninsured ophthalmologists have called OMIC with stories of physicians being dropped because they were doing refractive surgery or had just one claim. OMIC plans to continue underwriting physicians in the same prudent manner it has in the past, relying on its historical success of selecting insureds who ultimately contribute to loss results that are consistently better than the industry.

- Fewer discounts and lower dividends. Cash-strapped carriers may become less generous with premium discounts to raise much needed revenue. Last year, the surplus of all companies combined fell for the first time in recent history. Shrinking surplus and smaller or nonexistent reserve takedowns could mean lower dividend payouts in the future. OMIC’s surplus did not decrease last year and was maintained as the same conservative level as the previous year. OMIC also is continuing its cooperative ventures with a dozen state and subspecialty societies and provides a special 10% premium discount for participating in cosponsored risk management programs. As in the past, dividends will be determined each year based on annual performance results.

-

Claims costs will continue to increase unless controls are employed. Despite the cyclical nature of insurance markets and litigation, claims severity will continue to grow unabated unless doctors and carriers employ proven measures to stem the tide.

- Tort Reform — First and foremost, efforts to bolster state tort reform initiatives are critical to keeping claims indemnity under control. According to Jury Verdict Research, jury awards in malpractice cases jumped 7% in 1999, raising the median award to $800,000. During previous, “medical malpractice crises,” the most common factor associated with markedly improved loss experience was the existence of strong tort reform measures with an effective cap on noneconomic damages (pain and suffering).

- Risk Management — Despite the temptation to reduce costs by cutting back on operational expenses, such as risk management, carriers instead need to provide more resources for these activities. OMIC will continue to make its ophthalmic-specific risk management activities available to policyholders and members of the American Academy of Ophthalmology and anticipates extending these activities through the Internet and other means.

Why Some Carriers Can Withstand a Hard Market

Perhaps the silver lining in this hard market is that physicians and their professional liability carriers have been down this road before. What we’ve learned from previous hard markets is that such a condition is not so much a malpractice crisis as it is a cycle. Fortunately, cycles turn, but their duration can clearly be impacted by how quickly and how well we respond. Physicians who didn’t chase some of those irresistibly cheap rates in the past and stayed with a strong and reasonably priced insurer are now in a better position to ride out the hard market with their current carrier. Companies that previously engaged in predatory pricing tactics to gain market share may now have to play “catch-up” by significantly boosting rates to meet the future demands of rising claims. Others, such as OMIC and those physician-sponsored carriers that remained focused on their original mission and purpose, are likely to successfully ride out the current storm as well as provide opportunities to those doctors now forced to search for a new carrier that can better support their long-term insurance needs.

In the future, adverse market cycles might be broken if some carriers choose to learn from the past and resist the temptation to feed their egos and corporate appetite for market domination and growth at any cost.

Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

By Geri Layne Craddock, CLU

Vice President at Seabury & Smith, Washington, DC

[Digest, Summer 2001]

Have you ever stopped to consider how you would maintain your income if you were to suffer a disabling accident or illness? Many people believe that Social Security would be enough to protect them if they could not work. In fact, Social Security contains a very narrow definition of disability under which many situations are not covered. Additionally, Social Security benefits often are considerably less than private or group insurance benefits.

Workers’ compensation insurance should not be confused with disability insurance: workers’ compensation covers only disabilities that occur on the job. Disability plans offered by employers vary considerably in coverage length and percentage of salary that is covered. Many employers do offer disability insurance, but often it’s short-term coverage-generally one to five years-and may be grossly inadequate for those who suffer a long-term disability, such as paralysis or back injury.

At first glance, the cost of disability insurance might seem high. But it is important to remember that this is basic and essential insurance protection for people who rely on their regular income. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, one in five Americans were disabled in 1997.1 The American Council of Life Insurers maintains that a 35-year-old is six times more likely to become disabled than to die before he or she reaches age 65.2 Clearly, disability insurance may be even more essential than life insurance.

If you are interested in securing disability insurance, shop around and compare plans. Remember to weigh the cost against the potential benefits you would receive if you were unable to work for two, five, or twenty years. Examine these key elements as you compare policies:

Definition of “total disability.” This could be the most critical feature of your policy. Under many policies, you must be unable to perform any job for which you are qualified. One way to protect the educational investment you’ve made in your career is with own occupation coverage. Own occupation policies pay benefits if you are unable to engage in your own occupation even if you are able to return to work at a lower paying job that is not in your field. Some policies even consider a recognized medical specialty, such as ophthalmology, to be your occupation.

Length of benefits. Ideally, you should look for long-term coverage that protects you until age 65 even if you have to opt for lower benefits to keep the premiums more affordable.

Amount of coverage. To ensure that you have incentive to return to work, most plans set limits on the percentage of income you can insure, usually 50% to 60% of your total gross annual earnings. If you have an employer-provided plan that provides only limited coverage, consider purchasing supplemental coverage from another source.

Waiting period. The elimination or waiting period is the amount of time you must be disabled before your benefits begin-the shorter the waiting period, the higher the premiums.

Taxation of benefits. Benefits may be tax-free if you pay the premiums out-of-pocket, so check with your tax advisor.

Residual benefits. After a serious disability, many people return to work on a part-time basis for part-time pay. Residual or partial benefits can allow you to receive a combination of income and disability benefits until you fully recover. Without this feature, your benefits would most likely stop as soon as you return to work.

Financial strength of the insurance company. Find out as much as you can about the insurer. High ratings from A.M. Best Company, Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s Investors Service, or Fitch Ratings are good indicators of financial strength. Each of these independent rating companies have web sites where you can access information about various insurance companies.

Portable coverage. Having your own policy outside of your employee benefits allows you to move from practice to practice without fear of losing your coverage. Association-sponsored insurance is an excellent resource for that reason.

A valuable benefit of your Academy membership is your access to its many sponsored insurance programs, which have been individually tailored to meet the specific needs of ophthalmologists.

If you would like an information kit sent to you on the Academy’s Group Disability Income Plan,3 including plan features, cost, eligibility, renewability, limitations, and exclusions, call Seabury & Smith, the Academy’s life and health insurance administrator, at (888) 424-2308.

Notes:

- Taken from www.census.gov.

- Taken from www.insure.com/health/longtermdisability.html.

- Underwritten by New York Life Insurance Company, 51 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Browsing articles in "Coverage Issues"

Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

Digest, Fall 2001

Clarifications and guidelines already have been published to further elucidate the HIPAA statutes, with more to follow as health care providers try to make sense of HIPAA in relation to state privacy laws and their current practices. Simply stated, the law provides that a health care provider may not use or disclose protected health care information (PHI) except as required or permitted. Health care providers will need to provide patients with new blanket consent and specific authorization forms for the use of patient PHI. Ophthalmologists and anyone they share PHI with (such as companies providing accounting, billing, accreditation, or legal services) must enter into business associate agreements stating they will take appropriate safeguards in the transmission and use of PHI. When PHI is disclosed, providers may be require to de-identify the PHI or make reasonable efforts to disclose only the minimum information necessary to accomplish the intended purpose.

Under the new regulations, patients will have many affirmative rights that providers must facilitate. For example, patients can request restrictions on the use of their PHI; inspect, copy, and amend their PHI; and request an accounting of disclosures that providers have made of their PHI. In addition, health care providers must comply with certain administrative requirements, including: documenting their policies and procedures; appointing a privacy official; implementing privacy training; and creating administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect PHI.

HHS Encourage Cooperation

While much of this seems daunting, the U.S. Health & Human Services Department is encouraging cooperation and assistance to help providers achieve compliance – unlike the witch-hunt tactics of anti-fraud forces. Further, when assessing a practice’s reasonable compliance, the government will take into consideration a provider’s size and type of activities related to PHI. Punitive enforcement, at this point, is not a priority. However, civil fines, lawsuits, criminal fines, and imprisonment are tools the government can imply if it chooses to aggressively ferret out non-compliers.

What does this mean to OMIC insureds? First, it is essential that ophthalmologists understand the law and how it applies to their practice. Second, they must discern what steps to take to be compliant come spring 2003. Third, practitioners need to implement a protocol and then follow through on prescribed compliance procedures. Fourth, ophthalmologists should ensure that, as part of their insurance package, they are covered in the event the government targets their practice for violation of HIPAA regulations.

In light of the quickly approaching April 2003 deadline, OMIC is taking measures to protect and educate insureds. Risk management seminars will cover HIPAA privacy rules, and in early 2002, OMIC will make a HIPAA compliance program planning tool available to help insureds further understand the law and implement protocols to protect patient health care information.

Coverage for HIPAA Proceedings

Also in 2002, OMIC is expanding its fraud and abuse insurance program to cover HIPAA proceedings. OMIC’s Fraud & Abuse/HIPAA Privacy insurance will cover legal expenses civil proceedings instituted against the insured by a government entity alleging violations of HIPAA privacy regulations. OMIC’sComprehensive Fraud & Abuse/HIPAA Privacy insurance will cover legal expenses for proceedings instituted by a government entity alleging HIPAA privacy violations and resulting in administrative fines and penalties.

This HIPAA privacy coverage is in addition to both policies’ coverage of billing errors proceedings instituted by a government entity, third party payor, or qui tam (whistleblower) plaintiff under the False Claims Act. OMIC will provide a Fraud & Abuse/HIPAA Privacy policy free to its professional liability insureds $25,000 limits ($50,000 effective Jan 1, 2011). Higher limits to $100,000 are available for additional premium. OMIC offers American Academy of Ophthalmology members who are not OMIC professional liability insureds the opportunity to purchase this legal expense coverage as well. OMIC insureds and other Academy members also are eligible to purchase the Comprehensive Fraud & Abuse/HIPAA Privacy policy with limits ranging from $250,000 to $1,000,000. A $1,000 deductible applies to both policies.

For further information regarding OMIC’s new Fraud & Abuse/HIPAA Privacy program, please call the Sales Department at (800) 562-6642, ext. 654.

Coverage Issues, Coverage Question, General Insurance 101, Policy Issues // No Comments

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD, OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Spring 2004

Press coverage of the industrywide rise in medical malpractice claims frequency and severity is abundant. This has many insureds questioning whether their current limits of liability are adequate for the increasingly litigious environment in which they practice. To help insureds assess their coverage limits and needs, this article will address what is meant by limits of liability, how to select limits, and how changing limits affects coverage if a claim arises.

Your limits of liability are the maximum dollar amounts of indemnity OMIC will pay on your behalf as a result of covered claims. Indemnity is the amount of damages awarded in a lawsuit or agreed to in a settlement between the parties. OMIC will pay your reasonable defense costs in addition to your liability limits.

All OMIC insureds have two separate limits: the per claim, or “medical incident,” limit and the aggregate limit. The per claim limit is the maximum amount of indemnity OMIC will pay per insured for all damages caused by any one medical incident, or by any series of related medical incidents involving any one patient, regardless of the number of injuries, claimants or litigants, or the number of claims (notices, demands, lawsuits) that result. The aggregate limit, on the other hand, is the maximum amount OMIC will pay per insured for all claims made and reported during the policy period.

How to Select Limits

There are several factors to consider when selecting limits of liability. The limits you require may vary with changes in your state’s malpractice liability climate, the procedures you perform, and the makeup of your practice. Therefore, you should continually assess your current needs and corresponding coverage.

First, review the claims statistics for ophthalmologists. For example, as of February 2004, OMIC’s average indemnity payment was $130,166 and its largest indemnity payment was $1.8 million.

Second, consider your state’s risk relativity. When OMIC looks at risk relativity, it compares the number of insureds, the number of total claims, and the average indemnity paid per claim in each state. Under this analysis, due to the fact that OMIC has a large number of insureds in these states, OMIC’s highest claims activity is currently in California, Texas, and Illinois. For selecting limits, however, a better way to look at risk relativity might be to compare the average rate of claims per insured per state. OMIC insureds in Louisiana and Michigan currently experience the highest claims frequency.

Third, find out what liability limits your peers are carrying. The majority of OMIC insureds (65%) carry $1 million per claim/$3 million aggregate limits. Higher limits of $2 million per claim/and either $4 million or $6 million aggregate limits are selected by 21% of insureds. OMIC’s lowest offered limits of $500,000/$1.5 million are carried by 6% of insureds, while 4% select the highest limits OMIC offers, $5 million/$10 million. The remaining 4% of insureds carry other combinations of limits, including lower limits available exclusively to physicians who participate in their state’s patient compensation fund.

Fourth, consider the risks related specifically to your practice. Is your subspecialty one in which there is high claims frequency (e.g., cataract surgery) or large damage awards (e.g., neonatal care)? Do you share your coverage and limits with any ancillary employees or your sole shareholder corporation? On the other hand, have you ceased performing most surgical procedures or limited your practice to part time?

Fifth, assess your level of risk aversion. Would higher limits make you feel more secure because of the large indemnity cushion or less secure because of the “deep pockets” potentially discoverable by the plaintiff?

Finally, check with your hospital and state licensing board because they may specify the minimum amount of coverage you must carry. Also note that OMIC generally requires all OMIC-insured physiciansin practice together to carry the same liability limits. The practice’s legal entity cannot be insured at higher limits than those of the physicians.

Which Limits Apply to a Claim?

You should consider how changing your limits will affect the amount of indemnity available to you if a claim should arise. The limits of liability that apply to a claim are those limits that are in effect as of the date the claim is first made against you and first reported in writing to OMIC. In other words, if you increase or decrease your coverage after you’ve reported a claim made against you to OMIC, the limits that you carried when you reported the claim, not the new limits, will be applied to the claim.

Subject to underwriting review and approval, you may increase or decrease your limits of liability at any time during the policy period (although OMIC typically does not consider requests to change policy limits while a claim is pending). If you are in group practice, discuss this desired change with your practice administrator and partners. Your OMIC underwriter can provide you with the most recent OMIC data to help you determine which limits are appropriate for you. However, OMIC representatives are not in a position to offer you advice. If you need further assistance, please consult your personal attorney.

Claims Handling, Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD

OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Winter 2005

In order to properly investigate and defend a medical malpractice claim, the professional liability company and the insured must cooperate. The participation of the insured, who is the subject of the lawsuit and holds first-hand information about the incident, is crucial to his or her own defense. Without such cooperation and assistance, the insurer is severely handicapped and may even be precluded from advancing any defense.

While the litigation process nearly always progresses successfully, there are times when some insureds thwart the resolution of their claims by failing to cooperate. Insureds may believe they have done nothing wrong and therefore avoid any work to counter the plaintiffs’ allegations. Or, afraid of the consequences, they may keep vital information away from their defense attorney until late into the case development. They might not understand the importance of their presence at litigation proceedings (such as depositions, mediations, or arbitrations) and worry about taking time away from their practice. Some attempt to handle matters “on their own” by discussing the case with plaintiffs’ attorneys against the advice of defense counsel or making payments without their insurers’ consent. Others may not want to tarnish their record and thus refuse to participate in settlement talks even when there is strong evidence that the standard of care was breached.

Investigation and Defense

That is why many professional liability policies contain Cooperation Clauses that require insureds to assist in the defense of claims made against them. OMIC’s policy has such a clause and, broken down, it requires the insured’s assistance on three levels. First and foremost, the policy requires that insureds assist in resolving the claim brought by the patient by helping with the insurer’s investigation and defense of the claim at trial or through settlement, as appropriate. This includes producing medical records, spending time with defense counsel, coordinating the appearance of staff at depositions or at trial, and attending court proceedings.

Coordination of Payment

The second situation is related to the coordination of payment among various legally responsible parties or insurers. The insured is required to cooperate in enforcing a right of contribution (where the loss will be shared) or indemnity (where another party is responsible for the entire loss) against someone else liable for the claim. For example, an insured may give notice under his or her OMIC professional liability policy for an office premises claim that might also be covered under the insured’s business owners or general liability policy. In this case, OMIC would ask the insured to help coordinate the defense and resolution of this claim with the other insurer.

Unauthorized Payments

Finally, the insured is prohibited from making payments, incurring other expenses, or assuming any obligations except at the insured’s own cost and with OMIC’s permission. OMIC wants to participate in its insured’s defense and work with the insured to come to the best resolution possible for the insured and the injured party. If the insured does not allow OMIC to participate, OMIC cannot be responsible for expenses the insured incurs. One example of this situation is where an insured decides, without the advice of defense counsel, to hire a private detective to track a malingering patient. This can be problematic for the defense because the defendant may be compelled to provide the plaintiff with this information. If nothing was revealed through the investigation, this could undermine the insured’s defense. Another example is when an insured, believing it is in everyone’s best interest, makes an out-of-pocket payment to the patient after a lawsuit has been filed. Again, if the case proceeds, this early payment to the patient may jeopardize its defense.

Even with the notice of required cooperation provided in the policy, some insureds still may not comply. The risk for these insureds is that they may be prevented from recovering under their insurance policies for the particular claim or they may lose their coverage altogether.

Before the situation reaches this level, however, the OMIC Claims staff would work diligently to educate the insured regarding the importance of his or her participation and cooperation in the defense of the claim and discuss what specific action is needed from the insured to bring him or her into compliance.

OMIC understands the issues that may impede a physician’s cooperation with his or her insurer and has several ways to assist its insureds with the upset of a lawsuit. First, OMIC provides access to one-on-one personal counseling (under the direction of the defense counsel in order to preserve attorney-client privilege) to help insureds deal with the emotional impact of litigation. OMIC also offers litigation and deposition handbooks to help insureds better understand the process. Finally, OMIC’s policy pays insureds for reasonable expenses incurred at OMIC’s request in the investigation or defense of a claim and for earnings lost as a result of attendance at court hearings or trials (see policy provisions for details).

Articles, Coverage Issues, Practice Issues // No Comments

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD, OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Fall 2005

Over the past year, a task force of OMIC Board and staff members, John W. Shore, MD, Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, and Betsy Kelley, has been examining and revising underwriting requirements and risk management guidelines for coverage of outpatient surgical facilities (OSFs) insured by OMIC. OMIC’s Board of Directors assigned the task force to study scope of practice issues, state laws governing OSFs, and national, state, and local practice standards that establish a standard of care for cases performed in facilities insured by OMIC.

Types of Outpatient Surgical Facilities

First, the task force reviewed the type of facilities that OMIC insures. It found that OMIC insures a wide variety of OSFs with varying goals, scopes of business, and types of surgical procedures and anesthesia provided, including in-office surgical suites, refractive laser centers, and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). The types of anesthesia used in facilities insured by OMIC range from topical ocular anesthesia to full general anesthesia with invasive monitoring in high-risk surgical patients.

Some facilities are office-based treatment rooms where major eyelid and facial procedures are performed. Some of these offices permit outside surgeons of different specialties to utilize the in-office surgical suites. These surgeons, many of whom are not insured by OMIC, may perform major facial surgery in an unlicensed and loosely structured practice environment. This increases the vicarious liability shared by owners of the facility who are insured by OMIC.

Other surgical facilities are refractive surgical and laser centers. Surgical services in these facilities are usually limited to those requiring only topical anesthesia. The procedures are short in duration and the patients are relatively healthy. Some, however, are free-standing, licensed ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), where surgeons of almost every specialty provide surgical services to a full range of pediatric, teenage, adult, and geriatric patients.

Review Process

Then the task force studied all of OMIC’s claims, suits, and settlements involving OSFs. The task force analyzed nursing, anesthesia, pediatric, and surgical standards by national professional groups as well as state and federal laws, regulations, and directives. Information gathered was used to revise existing underwriting requirements and risk management guidelines for OMIC insured OSFs. In addition to being discussed by both the Underwriting and Risk Management Committees, the proposed changes were extensively reviewed by consultants and practicing ophthalmologists with the goal of providing meaningful, clinically relevant, and workable requirements that cover all types of OSFs insured by OMIC. An anesthesiologist was consulted to review the anesthesia, monitoring, and emergency response requirements.

New Requirements

As a result of its work, the task force produced a rewritten and reformatted “Outpatient Surgical Facility Application” (OSFA), which was adopted by the OMIC Board of Directors. All ambulatory surgery centers, laser surgery centers, and in-office surgical suites used by physicians other than the owners and their employees will be required to complete the new OSFA. The OSFA contains detailed information about OMIC’s underwriting requirements pertaining to patient selection, type of anesthesia/sedation, pre- and postoperative assessments and monitoring, and emergency response and equipment. These requirements will be implemented immediately for all new OSF applicants and effective upon renewal in 2006 for facilities currently insured by OMIC.

It is important that insureds abide by all underwriting and notification requirements specified in the OSFA, as failure to do so could result in uninsured risk or termination of coverage. Working with OMIC’s experienced underwriters should enable insureds to complete the application, understand its requirements to avoid any coverage problems, and obtain an extension for those facilities that need additional time to comply with the requirements. While OSFs that are licensed or accredited may already meet or exceed these requirements, we anticipate that some OSFs may need additional assistance to implement them. Most accredited OSFs will receive a 5% premium discount for meeting the accreditation standards. There are helpful resources listed at the end of the OSFA itself and OMIC’s risk manager is available for confidential consultations.

All OMIC-insured physicians help bear the cost of defending claims and paying indemnity. It is incumbent on the OMIC Board of Directors, therefore, to protect OMIC insureds as a whole by establishing requirements that it believes will best limit the company’s liability and by making certain that insureds abide by these requirements, while at the same time offering physicians the ability to practice in various settings.

Articles, Claims Handling, Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD

OMIC Staff Attorney

Digest, Winter 2006

Stress and worries abound when a patient sues or claims malpractice. One concern of insureds is the effect such action will have on their insurance coverage. Although claims can and sometimes do have an impact on insurability, understanding how a claim is handled at OMIC may provide insureds with some peace of mind.

Each department at OMIC has a different responsibility when a claim arises. Risk Management encourages insureds to be proactive and contact the department when medical incidents or issues occur so the risk manager can help them appropriately respond to the incident and incorporate any necessary changes in their practices or procedures. The Claims Department, in cooperation with the insured, wants to resolve the claim or lawsuit as efficiently and cost effectively as possible. Underwriting, meanwhile, must make certain that OMIC insures good risks. Insureds may therefore get several seemingly conflicting messages from the company depending on the status of their claim. Rest assured, however, that there are checks and balances in OMIC’s operational protocols to balance these priorities. Most importantly, OMIC’s Board of Directors is made up of ophthalmologists who not only approve company processes but also conduct claims and underwriting reviews.

Physician Review Panel

OMIC employs a continuous underwriting process, monitoring the claims activity of all insureds not only in anticipation of policy renewal, but also during the course of the insured’s coverage. Whether an insured’s claim(s) will warrant further review by OMIC’s physician review panel depends upon the insured’s history of claims frequency the number of claims or suits) and severity (indemnity amounts) and on the specific circumstances surrounding the claim(s). This could include indications that an insured is performing experimental procedures outside of the ordinary and customary practice of ophthalmology or has provided substandard care, followed poor informed consent techniques, or failed to cooperate during the claims-handling process. OMIC’s reviewers consider the insured’s entire claims experience, including his or her experience with insurance carriers other than OMIC.

After consideration, the physician review panel may determine one of several outcomes, including any of the following:

• The panel may continue the insured’s coverage without any conditions placed on his or her policy.

• The panel might continue the policy coverage with conditions, such as endorsing the policy to exclude coverage for certain activities or reducing the policy limits.

• The panel could also conclude that the insured’s risk profile falls outside of OMIC’s conservative underwriting standards, and that OMIC, therefore, is no longer in a position to cover the insured beyond the expiration of the insured’s policy.

• Finally, the panel, in rare circumstances, might determine that the insured’s actions warrant mid-term cancellation if the reasons for the cancellation fall within the policy provisions. These include fraud relating to a claim made under the policy and a substantial increase in “hazard insured against,” such as claims frequency or severity or unacceptable practice patterns.

Insureds are provided the opportunity to appeal coverage and termination decisions to the full Underwriting Committee. OMIC would not generally apply a policy surcharge (higher premium) because of claims experience.

Reporting a Claim or Medical Incident

The policy requires that an insured report to the Claims Department any claim or medical incident that occurs during the policy period which may reasonably be expected to result in a claim. The reporting of such an incident triggers coverage with OMIC. Even if the insured doesn’t obtain an extended reporting period endorsement (tail coverage) when he or she leaves OMIC, OMIC will continue to insure him or her for all covered claims and incidents reported while the policy was in force. An incident that does not develop into a claim will have no effect on the insured’s premium and will not be included in claims history reports provided to hospitals or other third parties. Claims or incidents reported to OMIC’s Risk Management Department are kept confidential: they are not shared with the Underwriting or Claims Departments without an insured’s permission and are not considered reported to OMIC for coverage purposes.

Finally, any indemnity payment made by OMIC on behalf of an insured will result in the removal of the insured’s loss-free credit upon renewal and for two policy terms. Then, if no further claims payments are made on behalf of the insured, the insured will begin earning loss free credits again, beginning at 1% and increasing 1% annually to a maximum discount of 5%.

Browsing articles in "Coverage Issues"

Articles, Coverage Issues // No Comments

Digest, Winter, 1996

Most physicians have heard these words: “Doctor, isn’t there anything else you can do? Some new treatment you can try?” Patients often perceive “new” treatments as better or less problematic than existing treatments and pleas for something “new” are particularly understandable when patients are faced with a terminal condition or loss of vision. Physicians generally look for proven treatments that will give their patients the best results with the least side effects. However, because of the tremendous psychological leverage of offering something “new,” physicians might be tempted to try unproven treatments to keep up with market forces. A good example of how market forces lead to such decisions might go something like this: “Mrs. Jones, you have the privilege of being in the right place at the right time. I am excited to inform you that I use the latest technology. The old method of correcting myopia is out and my new technique is in. In fact, because of my commitment to stay on the cutting edge, the laser I will be using to reshape your cornea was designed by me with the help of an engineer. This laser will correct your myopia in minutes.”

What assurance does Mrs. Jones have that the laser developed by her ophthalmologist is safe? Is it prudent for physicians to develop their own equipment or drugs for use on their patients? Who or what regulates physicians who do so?

Regulation of Physicians’ Practices

Production, sale, and clinical research of new drugs and medical devices are subject to regulation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Physicians and patients are protected to some degree when they use drugs or devices that have undergone the scrutiny of the FDA and received approval for marketing and sale. The known indications, hazards, and adverse effects of the approved device or drug are required to be included in the product labeling. The FDA can restrict the ability of a company to sell, manufacture, or import a drug or device and can impose a variety of other protective measures.

Ordinarily, physicians are not directly regulated in their use of drugs and devices in day-to-day practice but are expected to practice in a manner that is designed solely to insure the well-being of the patient. Unless a physician is himself marketing or selling a drug or device, or acting as an investigator in clinical research, the FDA generally does not oversee or interfere with a physician’s individual practice decisions.

It is a different matter when the physician is conducting clinical research. Research activity occurs when the clinician conducts a “systematic investigation” designed to develop or contribute to “generalizable knowledge” such as by testing a hypothesis, drawing conclusions, and developing a base of knowledge from the results, especially concerning safety or effectiveness of the product.

If a practicing physician departs from usual (standard) treatments for an individual patient, such as by using a self-made device, a modified device, or a marketed drug for an off-label use, such use does not in and of itself constitute “research.” However, the non-standard treatment might constitute a deviation from accepted standards of medical care. The standard of medical care, which is based upon what reasonable physicians in the same specialty would do at the same time under similar circumstances, is overseen by state and local medical boards, and indirectly, by malpractice lawsuits. Issues of deviation from standards of care are usually raised by patients and/or other practitioners filing a complaint with their state or local medical board or by patients bringing malpractice lawsuits. The medical board also may be informed of aberrant practice styles by federal agencies, such as the Health Care Financing Administration and Medicare Peer Review Organizations.

In addition, local hospitals and clinics oversee standards of medical practice through credentialing, peer review, and quality assurance procedures, which involve investigations of standards of care, identification of deficiencies, and establishment of minimum qualifications for privileges. This is why malpractice insurance companies request information relating to licensing sanctions, peer review proceedings, and denial or surrender of hospital privileges.

So Mrs. Jones is protected by community standards, state and local agencies and institutions, and to a lesser degree, by agencies of the federal government.

Physician Practice versus Investigational Use

A physician may manufacture his or her own equipment or devices solely for his own use in his practice, and may use approved products for non-approved (off-label) applications. In fact, off-label use of medication is quite common. Distinguishing off-label use of drugs or devices as part of a physician’s practice from “experimental” or “investigational” use may be difficult at times. If the new use is based on firm scientific rationale and sound medical evidence, and is not for the purpose of developing information about safety or efficacy (for example, to support a request for FDA approval of the new use or to support advertising of new uses for the product), the use generally will qualify as “the practice of medicine” rather than “investigational use.”

However, if the physician is gathering new information on multiple patients, particularly for publication purposes or to obtain approval for a new device or new use, it is probably considered research, and the physician must comply with the panoply of federal statutes and regulations governing all aspects of approval of new drugs and devices, including numerous requirements for the protection of human subjects in research. In most cases, the practitioner will be required to obtain approval from his or her local Institutional Review Board (IRB), a committee that operates under HHS and FDA regulations for the purpose of protecting the rights of research subjects. The FDA will not accept research data in support of a new drug or device application unless the research protocol and consent documents have been reviewed and approved by an IRB. Similarly, peer reviewed journals usually require documentation of IRB approval before research results will be accepted for publication.

The FDA does have the right to request tracking of marketed products and, although off-label uses in medical practice are not generally regulated, the FDA can disapprove an existing product, require additional warnings, and/or request a recall of a product if it is not happy with off-label uses of the product. Otherwise, regulation of a physician’s medical practice generally falls under the jurisdiction of the state and local agencies previously discussed.

Liability and Insurance Issues

If a physician develops a new device, such as a new ultrasound for phacoemulsification to use on patients in the office, he or she may well face additional liability exposure for problems resulting from the use of the device. Injuries caused by the use of non-approved devices and drugs generally fall within the scope of malpractice and general liability coverage, but a physician may be exposed to personal risk as well if the insurance policy does not cover the liability associated with such uses.

For this reason, it is a good idea to contact your professional liability carrier about potential liability exposure if any of your practice activities involve the use of a self-made instrument or off-label use of drugs or devices regardless of whether they have gone through IRB approval. OMIC, for example, has carefully considered the use of the excimer laser in photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and has developed internal guidelines intended to help reduce the increased professional liability and exposure to claims associated with their use.

Off-label applications of drugs also increase the potential for liability, although many drugs are widely used this way. A good example is mitomycin-C (Mutamycin) for glaucoma surgery. Mitomycin-C is FDA approved “for the use of disseminated adenocarcinoma in conjunction with other approved chemotherapeutic agents.” There is no mention of using this drug for pterygia or glaucoma surgery, and there is a long list of side effects for this drug, including pulmonary toxicity that does not appear to be dose related. Nevertheless, glaucoma surgeons are using this medication with increasing frequency, and even a few general ophthalmologists are using it to prevent the recurrence of pterygia following excision.

OMIC has considered the use of mitomycin-C and other off-label drugs (such as cyclosporin drops) and has this general recommendation:

When using a new or old drug in an approved manner, proceed with a green light. If it is an existing drug used in a non-approved manner (off-label), first consider whether its use poses significantly increased risks to the patient. Second, consider whether its use can be expected to bring good results without a higher complication rate. If it presents no more risk to the patient than that of daily living, proceed with its use; for example, the use of aspirin for anticoagulation after a central retinal vein occlusion. If there is an increased risk to the patient, ask yourself if at least a reasonable number of physicians in your specialty are using the treatment; that is, have peer reviewed articles been published supporting the use of the new treatment and is the treatment being used by a reasonable number of other practitioners with the same level of training as you?

Ophthalmologists are considered medical “specialists” and in most cases are held to a “national” rather than “local” standard of care. The same is true of subspecialists in various areas of ophthalmology. An ophthalmologist may face increased liability for off-label uses if a reasonable number of similar specialists or subspecialists are not using the same new treatment. An ophthalmologist whose patients experience more problems with off-label use of a medication than they would with standard methods of treatment might well be subject to professional criticism, and thus be exposed to malpractice liability and potential licensure or credentialing actions.

Additional Precautions

When considering new techniques, new devices, or new uses for approved drugs, practitioners need to think about taking additional measures to protect themselves as well as their patients. If you select a treatment for an individual patient with the intent that it will enhance the patient’s well-being, and there is sound medical evidence supporting the treatment, you are likely to be on solid ground. In such cases, FDA regulation is generally not controlling, and you probably will not need IRB approval unless the treatment so departs from standard practices that it may be considered experimental or investigational, or it presents significantly increased risks for the patient, and/or you wish to use the information for study purposes.

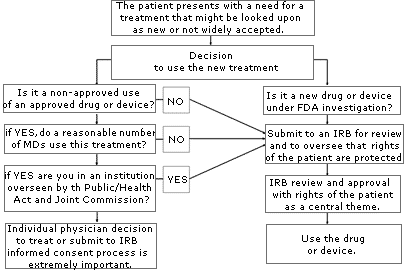

If you are uncertain about whether your use of a treatment or device might be considered “investigational” or “experimental,” consult your local IRB. An IRB is usually available at your local institution (some regional IRBs also exist) to review your proposed use and determine if it constitutes “research” requiring IRB approval. Similarly, if you are unsure whether the treatment has sufficient peer support or is simply too new, or if the literature is unclear, consider going through an IRB to help you with your decision. The flow diagram set forth on page A-78 may help you through the process of determining if you should submit your treatment proposal for IRB review.

Anytime you are considering unapproved uses of a device or drug, the informed consent process and its documentation, including treatment alternatives, should be thorough and specific in case you are later called upon to defend your decision to use non-standard treatments. If you have a specific area of concern, contact OMIC’s Risk Management Department for further information or referral to the appropriate resource or agency.

Coverage Issues, Policy Issues // No Comments

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Digest, Summer/Fall 2004

Allegations related to physician advertising are surfacing with increasing regularity in medical malpractice claims. In addition to alleging lack of informed consent, patients are using state consumer protection laws to claim that the physician defrauded them. This exposes the physician to punitive damages and other uninsured risks.

Physician advertising is regulated by state law as well as by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) under provisions of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA). The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) have issued guidelines to advise their members on relevant ethical and professional standards.

Advertising “includes any oral or written communication to the public made by or on behalf of an ophthalmologist that is intended to directly or indirectly request or encourage the use of the ophthalmologist’s professional medical services … for reimbursement” (ASCRS Guidelines). These guidelines therefore apply to print, radio, and television advertisements as well as to informational brochures, seminars, videos, and the Internet.

The FTCA prohibits deceptive or unfair practices related to commerce and “prohibits the dissemination of any false advertisement to induce the purchase of any food, drug, or device.” The FTCA and the professional guidelines state unequivocally that advertising for medical and surgical services must be truthful and accurate. It cannot be deceptive or misleading because of (1) a failure to disclose materials facts, or (2) an inability to substantiate claims – for efficacy, safety, permanence, predictability, success, or lack of pain – made explicitly or implicitly by the advertisement. It must balance the promotion of the benefits with a disclosure of the risks and be consistent with material included in the informed consent discussion and documents.

Lack of Informed Consent Allegations

When not carefully crafted, advertising runs the risk of overstating the possible benefits of a procedure and potentially misleading patients into agreeing to undergo surgery without fully understanding or appreciating the consequences and alternatives.

In a sense, an advertisement becomes a ghost-like appendage to boiler-plate informed consent forms. If an advertisement overstates the benefits, misrepresents any facts, or conflicts with other consent documentation or patient education material, it can potentially make a jury believe the physician may have overstepped the line of ethical propriety by creating unrealistic patient expectations. Legally, such a scenario might allow a jury to conclude the patient was not given a full and fair disclosure of the information needed to make a truly informed decision.

Punitive Damages and Other Uninsured Risks

Another pitfall for the ophthalmologist who markets medical services are state laws that may allow the plaintiff to ask for punitive damages, which could double or treble the amount of money awarded to the patient by the jury. Physicians should be particularly concerned about such allegations since most professional liability insurance policies, including OMIC’s, do not pay for such damages.

OMIC’s underwriting guidelines state that advertisements and marketing materials must not be misleading, false, or deceptive and must not make statements that guarantee results or cause unrealistic expectations. In addition, insureds are required to abide by FDA- and FTC-mandated guidelines and state law. OMIC has specific policy language limiting its professional liability coverage to defense costs for claims related to misleading advertisements. No payment of indemnity will be made.

Therefore, if a plaintiff is alleging medical malpractice and has an added allegation of fraud, your OMIC policy will provide defense for both the allegation of malpractice and fraud but would limit any indemnity payment to awards related to the medical malpractice allegation of the lawsuit.

2021: Updated advertising medical services

Coverage Issues, Coverage Question // No Comments

By Kimberly Wittchow, JD

OMIC Insurance and Group Products Associates

[Digest, Fall 1998]

In the litigious business environment of the 1990s, ophthalmic practices of all sizes are increasingly vulnerable to employment practices liability suits. Small and large practices alike are discovering that discrimination, sexual harassment and wrongful termination suits can wreck havoc on their bottom line, as even frivolous or unsubstantiated claims must be defended, often at considerable expense to the practice.

The media is replete with stories of employers being sued even those who insist they “did everything right.” Take, for instance, the female employee who resigned and sued her former employer for sexual harassment in part because one of the company’s owners gave her a scarf on Valentine’s Day. The company claimed it investigated the situation after the employee complained and acted to protect her from further incidents. Nevertheless, a federal court jury awarded the plaintiff $82,000, which the company had to pay, along with its own substantial legal defense costs.

A case in the South arose when an accounting clerk in a medical office threatened to sue, stating that she was having sex with one of the directors. Previously a virgin, the woman claimed that on some occasions sex was consensual, but at other times she was forced to participate. Rather than face a Bible Belt jury, the practice opted to settle for over $35,000.