As the number of patients diagnosed with cancer continues to rise, a concomitant increase in tumor-related skin disorders (TRSDs) can be expected. Management of these conditions, which can be challenging, is essential to the patient’s overall sense of comfort and well-being. In some cases, diagnosis of TRSDs may permit early detection of occult malignancy. In this chapter, tumor-associated skin conditions are divided into two groups:

- Generalized eruptions associated with internal malignancy

- Cancer-related genodermatoses.

These disorders are reviewed with respect to commonly associated malignancies (Table 21.1). Emphasis is placed on the more common examples of these uncommon conditions and potential management strategies are discussed.

Generalized Eruptions Associated with Internal Malignancy

Pruritus

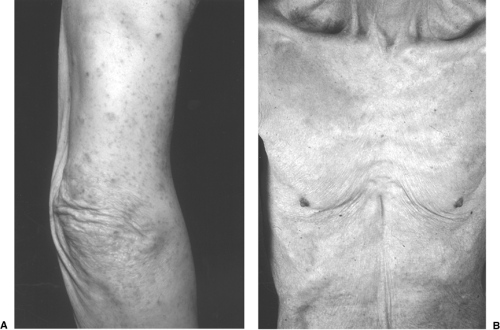

Pruritus, or itch, is often nonspecific. It is one of the most common complaints in the elderly patient and is most commonly secondary to xerosis (dry skin, Figure 21.1B) (1). However, intractable pruritus accompanied by severe excoriations may be an indicator of internal malignancy (1). This type of pruritus is most commonly encountered in Hodgkin’s lymphoma but may be observed with any internal malignancy (2). There are often no true primary lesions on examination but secondary changes including excoriations and subsequent lichenification and pigmentary alterations can be significant (Figure 21.1A). Pruritus has been reported in up to 25% of patients with Hodgkin’s disease and may be an indicator of less favorable prognosis when associated with fever or weight loss (2). Pruritus of Hodgkin’s disease is described as intense and burning and usually begins on a localized area.

Pruritus may also be a sign of cholestatic liver disease, renal disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, thyrotoxicosis, or diabetes (1). Infestation with scabies must also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

In contrast to the nonmalignant associations of localized pruritus, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the brain (3, 4), breast (5), colon (6), pancreas (7), and stomach (8) have been associated with generalized pruritus. Unilateral paroxysmal facial pruritus was reported as a presenting sign in two children with brain stem glioma (4). In both cases, pruritus resolved after radiation therapy was given for the glioma.

Intractable pruritus is best evaluated by a dermatologist, who can distinguish primary pruritus from pruritus secondary to some other cutaneous condition. Workup should include a thorough history and physical examination including baseline evaluation of complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests (LFTs), and chest x-ray. Skin biopsy of primary lesions, if present, may determine the cause of the pruritus.

| Table 21.1 Tumor-Associated Skin Disorders | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In addition, age-appropriate and symptom-directed cancer screening should be updated. Treatment options include oral antihistamines (especially sedating antihistamines), topical corticosteroids, and ultraviolet light therapy. Zylicz et al. have reported successful treatment of pruritus associated with cholestasis in disseminated cancer using buprenorphine with low-dose naloxone (9).

|

Sign of Leser-Trelat

The sign of Leser-Trelat is the sudden appearance of numerous seborrheic keratoses in association with internal malignancy. It has been most commonly associated with gastric carcinoma (10). The sign has been attributed separately to Edmund Leser and Ulysse Trelat (11, 12). Interestingly, this represents a misnomer because both individuals were actually observing cherry hemangiomas. In fact, it was Hollander who first emphasized the association between internal cancer and seborrheic keratoses in 1900 (13). Little is known about the pathogenesis of Leser-Trelat; however, some investigators point toward increases in tumor-derived growth factors (14).

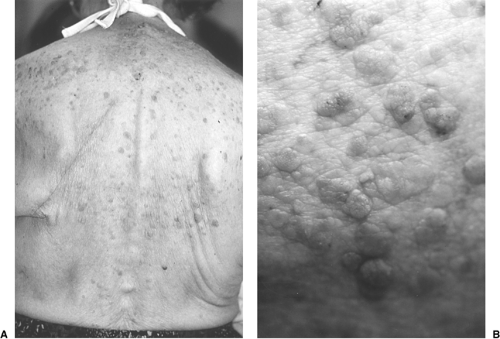

Seborrheic keratoses are benign lesions and are best described as waxy, hyperpigmented papules or plaques (Figure 21.2). They appear to be “stuck on” and look as though they might be easily peeled away from the surface of the skin. They are extremely common in older individuals and represent no danger to patients. The differential diagnosis may include benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions including lentigines, nevi, actinic keratoses, atypical nevi, pigmented Bowen’s disease, and melanoma. Diagnosis can be confirmed by simple skin biopsy performed by a dermatologist. Leser-Trelat is characterized by the sudden eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses and most commonly affects the back and chest, although the extremities, groin, and even the face may be affected (12). It must be emphasized that although seborrheic keratoses are common, the sudden appearance of numerous lesions or their appearance before the third decade is not common and should prompt further investigation. Vielhauer et al. have reported the diagnosis of occult renal cell carcinoma in a patient with Leser-Trelat (10). Curative nephrectomy was performed as a result of early diagnosis.

Further investigation in patients with Leser-Trelat should include a complete history and physical examination accompanied by routine blood studies including CBC, LFTs, chest x-ray, mammogram and pap smear for women, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for men. Endoscopic evaluation of the colon should also be considered, as should any symptom-directed diagnostic studies.

The presence of seborrheic keratoses itself is not dangerous to the patient and reassurance of this is necessary. If desired, they may be removed by curettage under local anesthesia with little risk of scarring. Other treatment methods include cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen and chemical cauterization with topical application of 70% trichloroacetic acid.

Erythema Gyratum Repens

Erythema gyratum repens is part of the group of gyrate erythemas (15). These are reactive, inflammatory dermatoses that share morphologic characteristics and have been described as “figurate,” “polycyclic,” and “serpiginous” in appearance (16). None of the gyrate erythemas has the characteristic appearance of erythema gyratum repens.

Erythema gyratum repens was first described by Gamel in 1952, who reported it in association with breast carcinoma (17). Since that time, the overwhelming instances of cases have been associated with internal malignancy (18).

On clinical examination, serpiginous, erythematous bands that take on a “wood grain” or “zebra-like” appearance (Figure 21.3) are seen. There is usually scaling associated with the lesions and there are often multiple bands. Lesions may be indurated and are likely to migrate over the course of hours. There may be associated pruritus. Unlike the characteristic clinical picture, histopathologic findings are nonspecific and may include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (15).

|

|

On suspicion of erythema gyratum repens, dermatologic consultation is required for confirmation. Because of the likelihood of association with internal malignancy, screening for internal malignancy should be performed. Standard screening laboratory and imaging studies should be performed with special attention toward ruling out cancer of the lung (18, 19). Although most commonly associated with lung cancer (20), erythema gyratum has been reported with breast and renal cancer (21) and, in rare cases, in the absence of malignancy (22). It is especially important to repeat screening tests periodically because the eruption may precede the onset of malignancy (23).

The most effective treatment is removal of the underlying tumor (19). Skin manifestations have resolved after removal of localized tumors or may persist until death in the face of widespread disease. Associated pruritus and inflammation may be relieved with oral antihistamines in combination with midpotency topical corticosteroids.

Hypertrichosis Lanuginosa Acquisita

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa acquisita, also referred to as malignant down, is characterized by the growth of fine, nonpigmented hair that occurs primarily on the face (23). It is most commonly associated with small cell and non–small cell carcinoma of the lung (24) and colorectal cancer (25) and has been reported with carcinomas of the kidney (26) and pancreas (27) and in metastatic melanoma (28). It has been associated with other conditions including shock, thyrotoxicosis, and porphyria and ingestion of drugs including cyclosporine, streptomycin, phenytoin, spironolactone, diazoxide, minoxidil, interferon, and corticosteroids (23).

The most effective treatment for malignant down is that it successfully treats the underlying tumor. Management of cosmesis may be attempted through electrolysis, depilatories, or shaving. Because the hairs are not pigmented, treatment with hair removal laser would likely be unsuccessful because lasers target melanin in the hair follicle. Treatment with eflornithine HCl cream (13.9%) applied to the affected area twice daily may be successful. This agent inhibits ornithine decarboxylase, a key hair cycle enzyme, and may result in noticeably diminished hair growth (29). The presence of hypertrichosis lanuginosa implies poor prognosis and a survival time of <2 years in most patients (23).

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema refers to cutaneous manifestations of the glucagonoma syndrome caused by a tumor of the pancreatic islet α-cells (30). The eruption begins as an erythematous patch involving the groin that spreads to the buttocks, perineum, thighs, and extremities (Figure 21.4).

The erythematous areas eventually undergo scaling and blister formation. Erosions occur subsequent to rupture of blisters and healing with induration and pigmentary change follows over the course of several weeks. This may follow a relapsing and remitting course and may be associated with stomatitis. The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, superficial candidiasis, bullous drug eruption, and pemphigus (30). Histologic findings include dyskeratotic epidermal cells with superficial epidermal necrosis (Figure 21.4D) (30). The diagnostic features include elevated plasma glucagon levels. Dermatologic consultation should be sought to confirm the diagnosis as well as to rule out other skin disorders that may mimic necrolytic migratory erythema. As with other paraneoplastic syndromes, effective tumor therapy results in improvement of cutaneous symptoms (31). Unfortunately, patients with necrolytic migratory erythema may have metastatic disease at presentation. There have been reports of successful treatment using the somatostatin analog octreotide. Jockenhovel et al. reported temporary resolution of cutaneous symptoms with octreotide but noted that the drug had no effect on tumor growth (32). Resolution may be noted as early as 1 week after beginning therapy but resistance can develop. Shepherd et al. reported successful treatment of cutaneous symptoms with intravenous amino acids (33). While waiting for response, denuded areas should be gently cleansed twice daily, covered with a bland emollient, and dressed with a nonstick bandage. Appropriate monitoring for secondary infection is indicated and is especially important in the hospitalized patient. Interestingly, one of the originally described patients was recently reported as a long-term survivor 24 years after diagnosis (34). Necrolytic migratory erythema has recently been reported in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome without glucagonoma or evidence of pancreatic disease (35).

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

Pemphigus is an immunologically mediated blistering disorder of the skin (36). The three main subtypes, based on target antigens, include pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus (including fogo selvagem, an endemic form), and paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). PNP is characterized by severe stomatitis, oral ulcers, and skin lesions with variable morphology (37, 38, 39). It is characteristically associated with hematologic malignancies, especially non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (38). It has also been associated with spindle cell sarcoma, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, thymoma (malignant and benign), Castleman’s tumor and pancreatic carcinoma (39). The pathogenesis centers on production of autoantibodies that attack components of the hemidesmosome and desmosome that function to link the epidermal cells to their basement membrane and to one another (38). Weakening of this scaffolding system renders the epidermal cells more susceptible to shearing forces, resulting in formation of blisters. The blisters rupture and result in erosive stomatitis, oral ulcers, and cutaneous erosions. In PNP there may be autoantibodies that recognize desmoglein 3, desmoglein 1, plakin proteins, and the hemidesmosomal BP230 (BPAg1) antigen (40).

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

DiarrheaConstipation

Metabolic Disorders in the Cancer Patient Communication During Transitions of Care Nutrition Support