Edit

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Medicine:Gender_dysphoria

Gender dysphoria (GD) is the distress a person feels due to a mismatch between their gender identity—their personal sense of their own gender—and their sex assigned at birth. The diagnostic label gender identity disorder (GID) was used until 2013 with the release of the DSM-5. The condition was renamed to remove the stigma associated with the term disorder. People with gender dysphoria commonly identify as transgender. Gender nonconformity is not the same thing as gender dysphoria and does not always lead to dysphoria or distress. According to the American Psychiatric Association, the critical element of gender dysphoria is "clinically significant distress". The causes of gender dysphoria are unknown but a gender identity likely reflects genetic and biological, environmental, and cultural factors. Treatment for gender dysphoria may include supporting the individual's gender expression or their desire for hormone therapy or surgery. Treatment may also include counseling or psychotherapy. Some researchers and transgender people support declassification of the condition because they say the diagnosis pathologizes gender variance and reinforces the binary model of gender.

binary model gender dysphoria gender identity

1. Signs and Symptoms

Distress arising from an incongruence between a person's felt gender and assigned sex/gender (usually at birth) is the cardinal symptom of gender dysphoria.[1][2]

Gender dysphoria in those assigned male at birth tends to follow one of two broad trajectories: early-onset or late-onset. Early-onset gender dysphoria is behaviorally visible in childhood. Sometimes gender dysphoria will stop for a while in this group and they will identify as gay or homosexual for a period of time, followed by recurrence of gender dysphoria. This group is usually sexually attracted to members of their natal sex in adulthood. Late-onset gender dysphoria does not include visible signs in early childhood, but some report having had wishes to be the opposite sex in childhood that they did not report to others. Trans women who experience late-onset gender dysphoria will usually be sexually attracted to women and may identify as lesbians or bisexual. It is common for people assigned male at birth who have late-onset gender dysphoria to cross-dress with sexual excitement. In those assigned female at birth, early-onset gender dysphoria is the most common course. This group is usually sexually attracted to women. Trans men who experience late-onset gender dysphoria will usually be sexually attracted to men and may identify as gay.[3][4]

Symptoms of GD in children include preferences for opposite sex-typical toys, games, or activities; great dislike of their own genitalia; and a strong preference for playmates of the opposite sex.[5] Some children may also experience social isolation from their peers, anxiety, loneliness, and depression.[6]

In adolescents and adults, symptoms include the desire to be and to be treated as the other sex.[5] Adults with GD are at increased risk for stress, isolation, anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, and suicide.[6] Transgender people are also at heightened risk for eating disorders[7] and substance abuse.[8]

2. Causes

The specific causes of gender dysphoria remain unknown, and treatments targeting the etiology or pathogenesis of gender dysphoria do not exist.[9] Evidence from studies of twins suggests that genetic factors play a role in the development of gender dysphoria[10][11] and gender identity is thought to likely reflect a complex interplay of biological, environmental, and cultural factors.[12]

3. Diagnosis

The American Psychiatric Association permits a diagnosis of gender dysphoria in adolescents or adults if two or more of the following criteria are experienced for at least six months' duration:[5]

- A strong desire to be of a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A strong desire to be treated as a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A significant incongruence between one's experienced or expressed gender and one's sexual characteristics

- A strong desire for the sexual characteristics of a gender other than one's assigned gender

- A strong desire to be rid of one's sexual characteristics due to incongruence with one's experienced or expressed gender

- A strong conviction that one has the typical reactions and feelings of a gender other than one's assigned gender

In addition, the condition must be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment.[5]

The DSM-5 moved this diagnosis out of the sexual disorders category and into a category of its own.[5] The diagnosis was renamed from gender identity disorder to gender dysphoria, after criticisms that the former term was stigmatizing.[13] Subtyping by sexual orientation was deleted. The diagnosis for children was separated from that for adults, as "gender dysphoria in children". The creation of a specific diagnosis for children reflects the lesser ability of children to have insight into what they are experiencing, or ability to express it in the event that they have insight.[14] Other specified gender dysphoria or unspecified gender dysphoria can be diagnosed if a person does not meet the criteria for gender dysphoria but still has clinically significant distress or impairment.[5] Intersex people are now included in the diagnosis of GD.[15]

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) lists several disorders related to gender identity:[16][17]

- Transsexualism (F64.0): Desire to live and be accepted as a member of the opposite sex, usually accompanied by a desire for surgery and hormonal treatment

- Gender identity disorder of childhood (F64.2): Persistent and intense distress about one's assigned gender, manifested prior to puberty

- Other gender identity disorders (F64.8)

- Gender identity disorder, unspecified (F64.9)

- Sexual maturation disorder (F66.0): Uncertainty about one's gender identity or sexual orientation, causing anxiety or distress

The ICD-11, which will come into effect on 1 January 2022, significantly revises classification of gender identity-related conditions.[18] Under "conditions related to sexual health", the ICD-11 lists "gender incongruence", which is coded into three conditions:[19]

- Gender incongruence of adolescence or adulthood (HA60): replaces F64.0

- Gender incongruence of childhood (HA61): replaces F64.2

- Gender incongruence, unspecified (HA6Z): replaces F64.9

In addition, sexual maturation disorder has been removed, along with dual-role transvestism.[20] ICD-11 defines gender incongruence as "a marked and persistent incongruence between an individual’s experienced gender and the assigned sex", with no requirement for significant distress or impairment.

4. Treatment

Treatment for a person diagnosed with GD may include psychological counseling, supporting the individual's gender expression, or hormone therapy or surgery. This may involve physical transition resulting from medical interventions such as hormonal treatment, genital surgery, electrolysis or laser hair removal, chest/breast surgery, or other reconstructive surgeries.[21] The goal of treatment may simply be to reduce problems resulting from the person's transgender status, for example, counseling the patient in order to reduce guilt associated with cross-dressing.[22]

Guidelines have been established to aid clinicians. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care are used by some clinicians as treatment guidelines. Others use guidelines outlined in Gianna Israel and Donald Tarver's Transgender Care.[23] Guidelines for treatment generally follow a "harm reduction" model.[24][25][26]

4.1. Children

The question of whether to counsel young children to be happy with their assigned sex, or to allow them to continue to exhibit behaviors that do not match their assigned sex—or to explore a gender transition—is controversial. Follow-up studies of children with gender dysphoria until 2013 consistently show that the majority of them will not remain gender dysphoric after puberty and will instead identify as gay or lesbian.[27][28][29] People are more likely to keep having gender dysphoria the more intense their gender dysphoria, cross-gendered behavior, and verbal identification with the desired/experienced gender are (i.e. stating that they are a different gender rather than wish to be a different gender).[30]

Professionals who treat gender dysphoria in children sometimes prescribe puberty blockers to delay the onset of puberty until a child is believed to be old enough to make an informed decision on whether hormonal or surgical gender reassignment is in their best interest.[31][32] The American Academy of Pediatrics state that "pubertal suppression in children who identify as TGD [transgender and gender diverse] generally leads to improved psychological functioning in adolescence and young adulthood."[33]

In the UK, a high court ruling in the case of Bell v Tavistock found that it was "doubtful" that a child under 16 could understand and weigh the consequences of such a decision, and thus was unlikely to be able to give informed consent.[34][35] A review commissioned by the UK Department of Health found that there was very low certainty of quality of evidence about puberty blocker outcomes in terms of mental health, quality of life and impact on gender dysphoria.[36] Similarly, the Finnish government commissioned a review of the research evidence for treatment of minors and the Finnish Ministry of Health concluded that there are no research-based health care methods for minors with gender dysphoria.[37] Nevertheless, they recommend the use of puberty blockers for minors on a case-by-case basis. In the United States , several states have introduced or are considering legislation that would prohibit the use of puberty blockers in the treatment of transgender children.[38] The American Medical Association, the Endocrine Society, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the American Academy of Pediatrics oppose these bans on puberty blockers for transgender children.[39][40][41][42][43]

4.2. Psychological treatments

Until the 1970s, psychotherapy was the primary treatment for gender dysphoria and generally was directed to helping the person adjust to their assigned sex. Psychotherapy is any therapeutic interaction that aims to treat a psychological problem. Psychotherapy may be used in addition to biological interventions, although some clinicians use only psychotherapy to treat gender dysphoria.[9] Psychotherapeutic treatment of GD involves helping the patient to adapt to their gender incongruence or to explorative investigation of confounding co-occurring[44][45][46][47] mental health issues. Attempts to alleviate GD by changing the patient's gender identity to reflect assigned sex have been ineffective.[48]:1741 Severe mental disorders and general identity confusion are the context for the majority of adolescent-onset cases. Treating these psychiatric comorbidities first may be called for, before drawing conclusions regarding gender identity.[44]

4.3. Biological treatments

Biological treatmentsbiological treatments.[50

Psychotherapy, hormone therapy, and sex reassignment surgery can be effective at treating GD when the WPATH Standards of Care 6 are followed.[48]:1570 A WPATH commissioned systematic review of the outcomes of hormone therapy "found evidence that gender-affirming hormone therapy may be associated with improvements in [quality of life] scores and decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms among transgender people." The strength of the evidence was low due to methodological limitations of the studies undertaken.[51] Those who choose to undergo sex reassignment surgery report high satisfaction rates with the outcome, though these studies have limitations including risk of bias (lack of randomization, lack of controlled studies, self-reported outcomes) and high loss to follow up.[52][53][54]

For adolescents, much is unknown, including persistence. Disagreement among practitioners regarding treatment of adolescents is in part due to the lack of long-term data.[44] Young people qualifying for biomedical treatment according to the Dutch model[55][56] (including having GD from early childhood on which intensifies at puberty and absence of psychiatric comorbidities that could challenge diagnosis or treatment) found reduction in gender dysphoria, although limitations to these outcome studies have been noted, such as lack of controls or considering alternatives like psychotherapy.[57]

More rigorous studies are needed to assess the effectiveness, safety, and long-term benefits and risks of hormonal and surgical treatments.[52] For instance, a 2020 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence[58] to determine whether feminizing hormones were safe or effective. Several studies have found significant long-term psychological and psychiatric pathology after surgical treatments.[52] The Swedish West Region commissioned Health Technology Assessment found in 2018 that the certainty of the evidence for sustained satisfaction with surgery was very low.[59]

5. Comorbidities

Among youth, around 20% to 30% of individuals heading to gender clinics meet the DSM criteria for a anxiety disorder,[60] though anxiety seemed to increase due to internalized transphobia.[61]

A review in 2014 stated that gender dysphoria symptoms in people with schizophrenia may arise due to delusionally changed gender identity or appear regardless of psychotic process.[62]

A widely held view among clinicians is that there is an over-representation of neurodevelopmental conditions amongst individuals with GD, although this view has been questioned.[63] Studies on children and adolescents with gender dysphoria have found a high prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) traits or a confirmed diagnosis of ASD. Adults with gender dysphoria attending specialist gender clinics have also been shown to have high rates of ASD traits or an autism diagnosis as well.[64] It has been estimated that children with ASD were over four times as likely to be diagnosed with GD,[63] with ASD being reported from 6% to over 20% of teens referring to gender identity services.[65]

6. Epidemiology

The DSM-5 estimates that about 0.005% to 0.014% of people assigned male at birth and 0.002% to 0.003% of people assigned female at birth are diagnosable with gender dysphoria.[66]

According to Black's Medical Dictionary, gender dysphoria “occurs in one in 30,000 male births and one in 100,000 female births.”[67] Studies in European countries in the early 2000s found that about 1 in 12,000 natal male adults and 1 in 30,000 natal female adults seek out sex reassignment surgery.[68] Studies of hormonal treatment or legal name change find higher prevalence than sex reassignment, with, for example a 2010 Swedish study finding that 1 in 7,750 adult natal males and 1 in 13,120 adult natal females requested a legal name change to a name of the opposite gender.[68]

Studies that measure transgender status by self-identification find even higher rates of gender identity different from sex assigned at birth (although some of those who identify as transgender or gender nonconforming may not experience clinically significant distress and so do not have gender dysphoria). A study in New Zealand found that 1 in 3,630 natal males and 1 in 22,714 natal females have changed their legal gender markers.[68] A survey of Massachusetts adults found that 0.5% identify as transgender.[68][69] A national survey in New Zealand of 8,500 randomly selected secondary school students from 91 randomly selected high schools found 1.2% of students responded "yes" to the question "Do you think you are transgender?".[70] Outside of a clinical setting, the stability of transgender or non-binary identities is unknown.[68]

Research indicates people who transition in adulthood are up to three times more likely to be male assigned at birth, but that among people transitioning in childhood the sex ratio is close to 1:1.[71] The prevalence of gender dysphoria in children is unknown due to the absence of formal prevalence studies.[30]

7. History

Neither the DSM-I (1952) nor the DSM-II (1968) contained a diagnosis analogous to gender dysphoria. Gender identity disorder first appeared as a diagnosis in the DSM-III (1980), where it appeared under "psychosexual disorders" but was used only for the childhood diagnosis. Adolescents and adults received a diagnosis of transsexualism (homosexual, heterosexual, or asexual type). The DSM-III-R (1987) added "Gender Identity Disorder of Adolescence and Adulthood, Non-Transsexual Type" (GIDAANT).[72][73][74]

8. Society and Culture

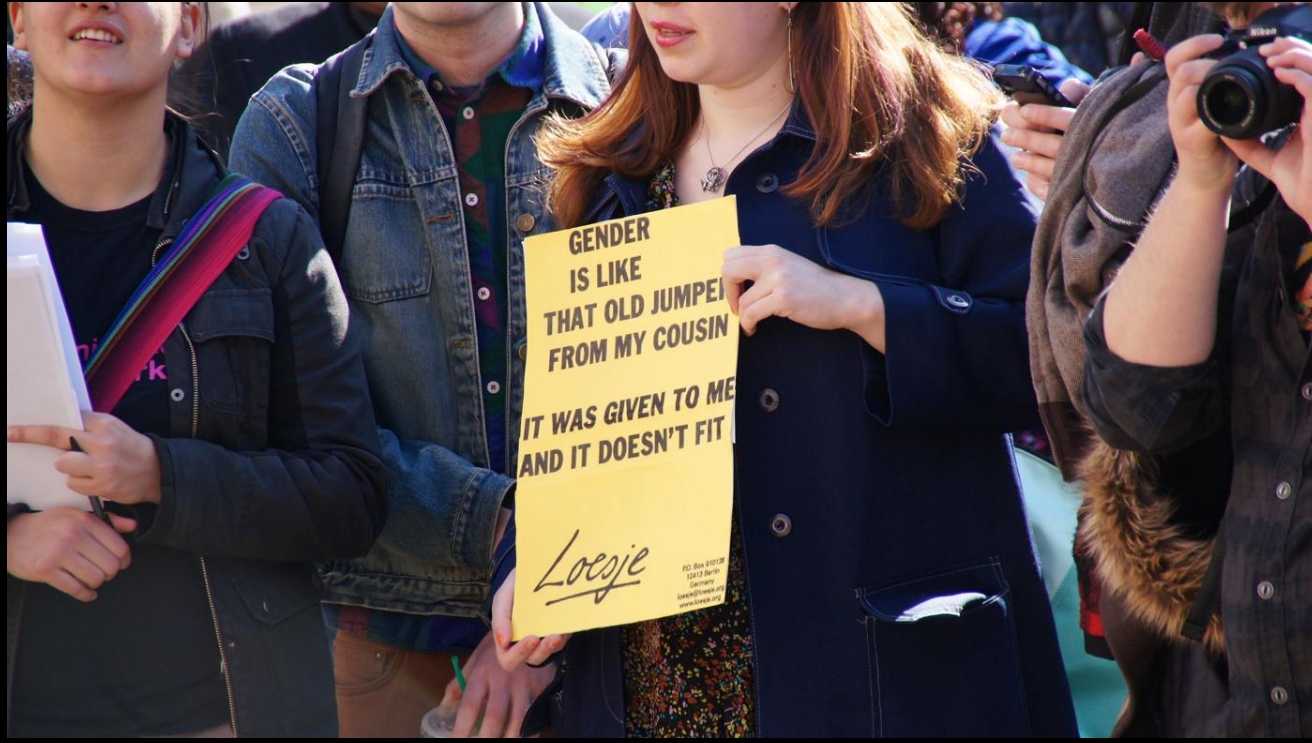

Researchers disagree about the nature of distress and impairment in people with GD. Some authors have suggested that people with GD suffer because they are stigmatized and victimized;[75][76] and that, if society had less strict gender divisions, transgender people would suffer less.[77]

Some controversy surrounds the creation of the GD diagnosis, with Davy et al. stating that although the creators of the diagnosis state that it has rigorous scientific support, "it is impossible to scrutinize such claims, since the discussions, methodological processes, and promised field trials of the diagnosis have not been published."[15]

Some cultures have three defined genders: man, woman, and effeminate man. For example, in Samoa, the fa'afafine, a group of feminine males, are entirely socially accepted. The fa'afafine do not have any of the stigma or distress typically associated in most cultures with deviating from a male/female gender role. This suggests the distress so frequently associated with GD in a Western context is not caused by the disorder itself, but by difficulties encountered from social disapproval by one's culture.[78] However, research has found that the anxiety associated with gender dysphoria persists in cultures, Eastern or otherwise, which are more accepting of gender nonconformity.[79]

In Australia, a 2014 High Court of Australia judgment unanimously ruled in favor of a plaintiff named Norrie, who asked to be classified by a third gender category, 'non-specific', after a long court battle with the NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages.[80] However, the Court did not accept that gender was a social construction: it found that sex reassignment "surgery did not resolve her sexual ambiguity".[80]:para 11

8.1. Classification as a Disorder

The psychiatric diagnosis of gender identity disorder (now gender dysphoria) was introduced in DSM-III in 1980. Arlene Istar Lev and Deborah Rudacille have characterized the addition as a political maneuver to re-stigmatize homosexuality.[81][82] (Homosexuality was removed from DSM-II in 1974.) By contrast, Kenneth Zucker and Robert Spitzer argue that gender identity disorder was included in DSM-III because it "met the generally accepted criteria used by the framers of DSM-III for inclusion."[83] Some researchers, including Spitzer and Paul J. Fink, contend that the behaviors and experiences seen in transsexualism are abnormal and constitute a dysfunction.[84] The American Psychiatric Association stated that gender nonconformity is not the same thing as gender dysphoria,[85] and that "gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder. The critical element of gender dysphoria is the presence of clinically significant distress associated with the condition."[86]

Individuals with gender dysphoria may or may not regard their own cross-gender feelings and behaviors as a disorder. Advantages and disadvantages exist to classifying gender dysphoria as a disorder.[87] Because gender dysphoria had been classified as a disorder in medical texts (such as the previous DSM manual, the DSM-IV-TR, under the name "gender identity disorder"), many insurance companies are willing to cover some of the expenses of sex reassignment therapy. Without the classification of gender dysphoria as a medical disorder, sex reassignment therapy may be viewed as a cosmetic treatment, rather than medically necessary treatment, and may not be covered.[88] In the United States, transgender people are less likely than others to have health insurance, and often face hostility and insensitivity from healthcare providers.[89]

The DSM-IV-TR diagnostic component of distress is not inherent in the cross-gender identity; rather, it is related to social rejection and discrimination suffered by the individual.[78] Psychology professor Darryl Hill insists that gender dysphoria is not a mental disorder, but rather that the diagnostic criteria reflect psychological distress in children that occurs when parents and others have trouble relating to their child's gender variance.[84] Transgender people have often been harassed, socially excluded, and subjected to discrimination, abuse and violence, including murder.[6][77]

In December 2002, the British Lord Chancellor's office published a Government Policy Concerning Transsexual People document that categorically states, "What transsexualism is not ... It is not a mental illness."[90] In May 2009, the government of France declared that a transsexual gender identity will no longer be classified as a psychiatric condition,[91] but according to French trans rights organizations, beyond the impact of the announcement itself, nothing changed.[92] Denmark made a similar statement in 2016.[93]

In the ICD-11, GID is reclassified as "gender incongruence", a condition related to sexual health.[19] The working group responsible for this recategorization recommended keeping such a diagnosis in ICD-11 to preserve access to health services.[20]

8.2. Gender Euphoria

Gender euphoriagender dysphoria.[68][94

References

- Zucker, Kenneth J.; Lawrence, Anne A.; Kreukels, Baudewijntje P.C. (2016). "Gender Dysphoria in Adults". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12: 217–247. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093034. PMID 26788901. "[For DSM-5] a reconceptualization was articulated in which 'identity' per se was not considered a sign of a mental disorder. Rather, it was the incongruence between one’s felt gender and assigned sex/gender (usually at birth) leading to distress and/or impairment that was the core feature of the diagnosis.". https://dx.doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev-clinpsy-021815-093034

- Lev, Arlene Istar (2013). "Gender Dysphoria: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back". Clinical Social Work Journal 41 (3): 288–296. doi:10.1007/s10615-013-0447-0. "[Despite some misgivings], I think that the change in nomenclature from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5 is a step forward, that is, removing the concept of gender as the site of the disorder and placing the focus on issues of distress and dysphoria.". https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10615-013-0447-0

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 451–460. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. https://archive.org/details/diagnosticstatis0005unse/page/451. ;

- "A Review of the Status of Brain Structure Research in Transsexualism". Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (7): 1615–48. October 2016. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0768-5. PMID 27255307. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&;artid=4987404

- American Psychiatry Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Washington, DC and London: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 451–460. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. https://archive.org/details/diagnosticstatis0005unse/page/451. ;

- Davidson, Michelle R. (2012). A Nurse's Guide to Women's Mental Health. Springer Publishing Company. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8261-7113-9.

- "Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students". The Journal of Adolescent Health 57 (2): 144–9. August 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003. PMID 25937471. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&;artid=4545276

- Harmon, A., & Oberleitner, M. G. (2016). Gender dysphoria. In Gale (Ed.), Gale encyclopedia of children's health: Infancy through adolescence (3rd ed.). Farmington, MI: Gale.

- Gijs, L; Brawaeys, A (2007). "Surgical Treatment of Gender Dysphoria in Adults and Adolescents: Recent Developments, Effectiveness, and Challenges". Annual Review of Sex Research 18 (178–224).

- "Gender identity disorder in twins: a review of the case report literature". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 9 (3): 751–7. March 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02567.x. PMID 22146048. "Of 23 monozygotic female and male twins, nine (39.1%) were concordant for GID; in contrast, none of the 21 same‐sex dizygotic female and male twins were concordant for GID, a statistically significant difference (P = 0.005)... These findings suggest a role for genetic factors in the development of GID.". https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1743-6109.2011.02567.x

More

©Text is available under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons-Attribution ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy.