“Deep periwinkle, plumbago, or the electric blue of the gloaming hour from his native England”: Those are the words of a professor with the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Peter Gizzi, trying to pin down the exact variation of blue in one of Trevor Winkfield’s paintings. What is it about Mr. Winkfield’s art, currently the subject of an exhibition at Tibor de Nagy Gallery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, that makes his admirers wax poetic?

Perhaps it’s because so many of them are, in fact, poets. Mr. Winkfield has actively sought their company since arriving on these shores in 1969. Among his admirers, friends, and collaborators are a veritable who’s-who list of like-minds, including John Ashbery, Ron Padgett, Barbara Guest, Harry Matthews, John Yau, and Mr. Gizzi. In 2015, Poets House in Lower Manhattan feted Mr. Winkfield with an exhibition underscoring his relationships with those of poetic mien.

The figure who is the clearest coefficient of Mr. Winkfield’s wry brand of absurdism is Raymond Roussel (1877-1933), the French writer whose poems and plays beggar casual description. The Surrealists were fans of Roussel’s verse, as were the likes of Andre Breton and Marcel Duchamp. His literary approach was ornate, playful, and bound by an elaborate set of rules. Roussel likened his process of “dislocation” and “extraction” to both creating and deciphering a rebus.

Mr. Winkfield is more than a fan of Roussel: He edited, translated and provided the cover art for “How I Wrote Certain of My Books,” the poet’s posthumously published explanation of how he did what he did. The name of Mr. Winkfield’s current exhibition, “The Solitary Radish,” recalls Roussel in its cockeyed anthropomorphism. The titles of the paintings are similarly oddball in their allusions: “Montezuma, Found at Last,” “Guardian of the Broom Closet,” and “Plant Wrongs.”

Titles are only as good as the paintings to which they are appended, and Mr. Winkfield’s paintings are very good indeed. Fans of the artist won’t be surprised by the new canvases, confirming, as they do, that Mr. Winkfield was ever thus. But if Ralph Waldo Emerson was right in that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” Mr. Winkfield proves that consistency can also be conducive to a deepening of vision. As for fools and hobgoblins: the paintings are rife with them. Mr. Winkfield wouldn’t have it any other way.

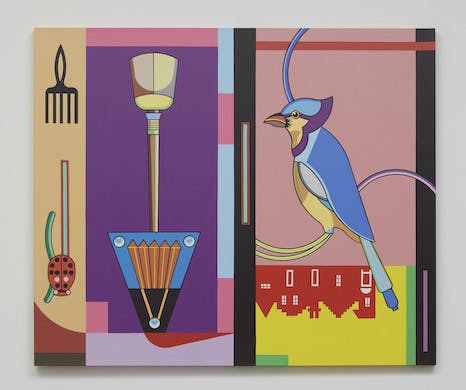

A colleague describes Mr. Winkfield’s pictures as what might happen if the Jack of Hearts had an acid trip while watching “Yellow Submarine” on a continuous loop. The artist does paint his forms with a deliberation reminiscent of the stylistic conventions of face cards, and his imagery is, to put it mildly, fanciful. In “Guardian of the Broom Closet,” a bluejay, a ladybug, an afro comb, a standing lamp, and an upended silhouette of townhouses are set within a geometric scaffolding reminiscent of the mid-century abstractions of Burgoyne Diller.

Still, Mr. Winkfield is nobody’s idea of a long-haired maven of psychedelic persuasion. His canvases are meted out with significant measure. The compositions are flat and graphic, and their structures recall not only High Modernist abstraction but game boards and, at moments, wallpaper patterning. Mr. Winkfield’s jerry-rigged accumulations of icons, emblems, and thingummies are distributed in a manner that is no less jaunty for being heraldic. High spirits coexist with dutiful propriety, comedy with classicism. Mr. Winkfield pulls this off with a cheeky elan.

In a 2017 interview with journalist Lee Smith, Mr. Winkfield talked of his experience looking at a canvas by the 17th-century painter Antoine Watteau: “My nose,” he recalled, “was 12 inches from the surface for the better part of an hour.” Whereupon, the artist extolled Watteau’s ability to relate complex narrative incidents through “incredibly economical” pictorial means.

Mr. Winkfield is too self-effacing a temperament to encourage comparisons with a French master, but his paintings operate on a similar wavelength. They’re just the ticket for gallery-goers who favor their hijinks cunningly distilled and consummately rendered.